Cross-platform, cross-architecture DKOM detection

To know if your system is compromised, you need to find everything that could run or otherwise change state on your system and verify its integrity (that is, check that the state is what you expect it to be).

“Finding everything” is a bold statement, particularly in the realm of computer security, rootkits, and advanced threats. Is it possible to find everything? Sadly, the short answer is no, it’s not. Strangely, the long answer is yes, it is.

By defining the execution environment at any point in time, predominantly through the use of hardware-based hypervisor or virtualization facilities, you can verify the integrity of that specific environment using cryptographically secure hashing.

Despite the relative ease of hash integrity checks, applying them to memory presents a number of significant challenges; the most difficult being identifying all of the processes that may execute on a system. System process control registers describe the virtual-to-physical memory layout. Only after all processes are found can integrity verification of code, data, and static/structural analysis be conducted.

“DKOM is one of the methods commonly used and implemented by Rootkits, in order to remain undetected, since this the main purpose of a rootkit.” – Harry Miller

Finding Processes by Page Table Detection

When an OS starts up a process, it establishes the ability for virtual memory to be used (to enable memory protection), by creating a page table. The page table is itself a single page of physical memory (0x1000 bytes). It is usually allocated by way of a cache-optimized mechanism, which makes locating it somewhat complicated. Fortunately, we can identify a page table by understanding several established (hardware) requirements for its construction.

Even if an attacker significantly modifies and attempts to hide from standard logical object scanning, there is no way to evade page-table detection without significantly patching the OS fault handler. A major benefit to a DKOM rootkit is that it avoids code patches, that level of modification is easily detected by integrity checks and is counter to the goal of DKOM. DKOM is a codeless rootkit technique, it runs code without patching the OS to hide itself, it only patches data pointers.

IOActive released several versions of this process detection technique. We also built it into our memory integrity checking tools, BlockWatch™ and The Memory Cruncher™.

Process–based Page Table Detection

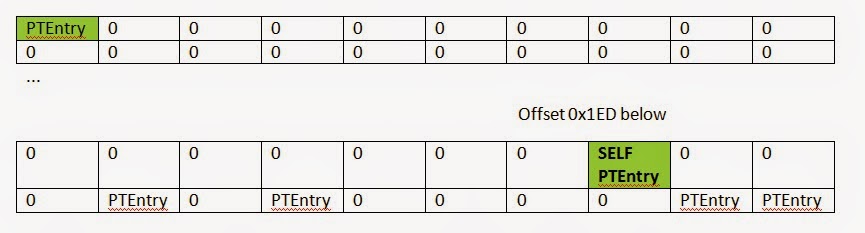

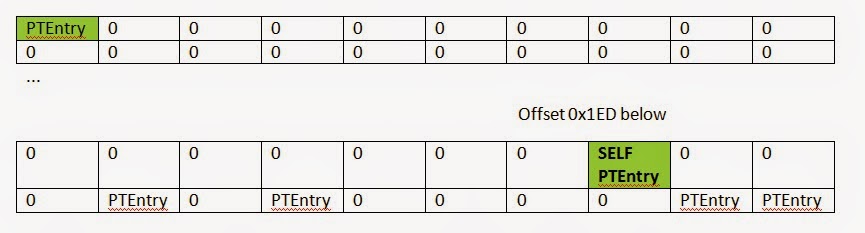

Any given page of memory could be a page table. Typically a page table is organized as a series of page table entries (PTEs). These entries are usually traversed by selecting some bits from a virtual address and converting them into a series of table lookups.

The magic of this technique comes from the propensity of all OS (at least Windows, Linux, and BSD) to organize their page tables into virtual memory. That way they can use virtual addresses to edit PTEs instead of physical memory addresses.

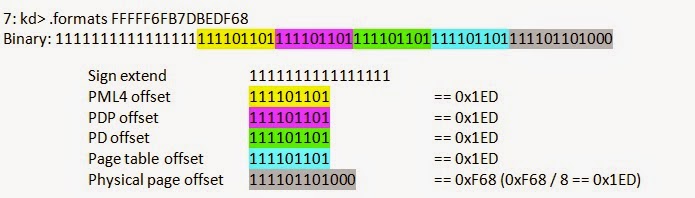

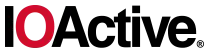

By making all of the offsets the same with the entry at that offset pointing back to the page table base value (CR3), the page table can essentially be accessed through this special virtual address. Refer to the

Linux article for an exhaustive explanation of why this is useful.

Physical Memory Page

If we consider any given page of random physical memory, we can detect the following offsets as a valid PTE. Windows has proven to consume, for every process, entry 0, entry 0x1ED (self map), and a couple of additional kernel regions (consistent across all Win64 versions).

PTE Format

typedef struct _HARDWARE_PTE {

ULONGLONG Valid : 1; Indicates hardware or software handling (Mode 1 and 2)

ULONGLONG Write : 1;

ULONGLONG Owner : 1;

ULONGLONG WriteThrough : 1;

ULONGLONG CacheDisable : 1;

ULONGLONG Accessed : 1;

ULONGLONG Dirty : 1;

ULONGLONG LargePage : 1; Mode 2

ULONGLONG Global : 1;

ULONGLONG CopyOnWrite : 1;

ULONGLONG Prototype : 1; Mode 2

ULONGLONG reserved0 : 1;

ULONGLONG PageFrameNumber : 36; PFN, always incrementing (Mode 1 and 2)

ULONGLONG reserved1 : 4;

ULONGLONG SoftwareWsIndex : 11; Mode 2

ULONGLONG NoExecute : 1;

} HARDWARE_PTE, *PHARDWARE_PTE;

By checking the physical memory offsets we expect, extracting a candidate entry, we can determine if the physical page is a valid page table. There are a number of properties we understand about physical memory: the address of page frame number (PFN) will always increase from earlier pages and will not be larger than the current linear position + memory gap ranges.

What About Shadow Walker Tricks?

Shadow walker abuses the nature of the TLB of a running system. Execution may occur at a different address than when reading. If you look/scan/check memory, the address will be cloaked onto what you expect when reading, while execution will actually occur somewhere different.

This is one reason why we analyze memory extracted from a hypervisor “guest” OS snapshot. Analyzing memory from behind a hypervisor establishes a “semantic gap” that ensures our static memory analysis includes all possible memory pages, unaffected by split I/D TLB games.

What About Hardware Rootkits?

Using a hypervisor makes verifying device memory easy. Verification at the host or physical layer is extremely complicated. Different hardware vendors have vastly different ways to extract and interact with firmware, UEFI may be verifiable with Mitre’s Copernicus2 or other tools.

In order for a hypervisor to be effected by a hardware rootkit, the hypervisor has to have been “escaped”, which is currently a rare and valuable exploit. It is probably not worth risking such a valuable exploit for a hardware rootkit that can be mitigated by the network. Extracting physical system memory in a consistent way (immune to attack and evasion) has historically been very hard.

If you are concerned about hardware rootkits, there are some extreme techniques that may help.

IOActive has Everything

Now that we have established a method for finding everything, the next task is relatively simple. Do some checking to ensure that what we found is what we expected. Using cryptographically secure hash checks in a whitelist fashion is a straight-forward and hard-to-attack technique for integrity verification.

IOActive’s current solution, BlockWatch™, does just that. It manages memory extraction and hash checking that testifies to what we have found.

Weird Rootkits

I classify “weird rootkits” as anything from a

RoP-based rootkit to some form of script injection or

anything else where the attacker can coerce an application to behave in an unexpected (and rootkit-like) way.

Detecting a RoP is actually quite easy (stack checking a memory snapshot). I covered some of this in a CanSecWest presentation I gave earlier this year. Each return address on a stack must be preceded by a call instruction. You can then validate that the opcode exists and the return address is not spurious (as is the case for a RoP attack). RoP stacks are also exceedingly large and are atypical of normal threads.

What about other attacks, rootkits implemented in server scripts and anything else? If we have found the address spaces for all of the processes and are able to validate the integrity of all of the kernel code, then any scripts or weird rootkits will be observable through normal profiling and logging interfaces.

Summary

By leveraging the unique ability of a hypervisor to expose the physical memory of a system in a way that is consistent (not modified by an attacker), we can use a high-assurance process detection technique combined with integrity checking to detect any rootkit.

Additional References

- BlockWatch™

- DEF CON 22 Presentation: “Weird-machine Motivated Practical Page Table Shellcode & Finding Out What’s Running on Your System

- PMODUMP

- Windows Debugging Blog on understanding !PTE