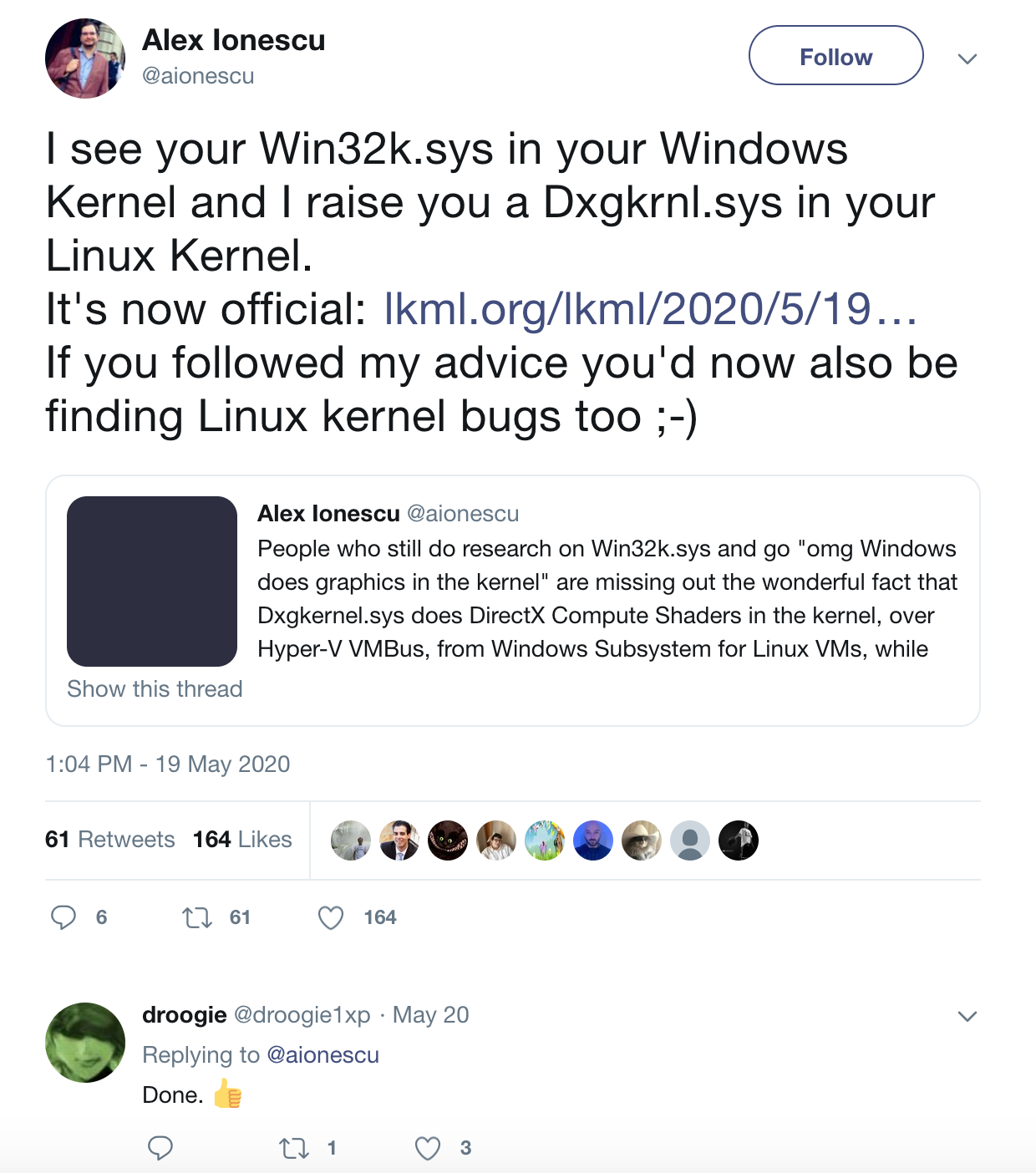

The year 2020 has been a disaster of biblical proportions. Old Testament, real wrath of God type stuff. Fire and brimstone coming down from the skies! Rivers and seas boiling! Forty years of darkness, earthquakes, volcanoes, the dead rising from the grave! Human sacrifices, dogs and cats living together…mass hysteria and reporting Linux kernel bugs to Microsoft!? I thought I would write up a quick blog post explaining the following tweet and walk through a memory corruption flaw reported to MSRC that was recently fixed.

Back in May, before Alex Ionescu briefly disappeared from the Twitter-verse causing a reactionary slew of conspiracy theories, he sent out this tweet calling out the dxgkrnl driver. That evening it was brought to my attention by my buddy Ilja van Sprundel. Ilja has done a lot of driver research over the years, some involving Windows kernel graphics drivers. The announcement of dxgkrnl was exciting and piqued our interest regarding the new attack surface it opens up. So we decided to quickly dive into it and race to find bugs. When examining kernel drivers the first thing I head to are the IOCTL (Input/Output Control) handlers. IOCTL handlers allow users to communicate with the driver via the ioctl syscall. This is a prime attack surface because the driver is going to be handling userland-provided data within kernel space. Looking into drivers/gpu/dxgkrnl/ioctl.c the following function is at the bottom, showing us a full list of the IOCTL handlers that we want to analyze.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 | void ioctl_desc_init(void) { memset(ioctls, 0, sizeof(ioctls)); SET_IOCTL(/*0x1 */ dxgk_open_adapter_from_luid, LX_DXOPENADAPTERFROMLUID); SET_IOCTL(/*0x2 */ dxgk_create_device, LX_DXCREATEDEVICE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x3 */ dxgk_create_context, LX_DXCREATECONTEXT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x4 */ dxgk_create_context_virtual, LX_DXCREATECONTEXTVIRTUAL); SET_IOCTL(/*0x5 */ dxgk_destroy_context, LX_DXDESTROYCONTEXT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x6 */ dxgk_create_allocation, LX_DXCREATEALLOCATION); SET_IOCTL(/*0x7 */ dxgk_create_paging_queue, LX_DXCREATEPAGINGQUEUE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x8 */ dxgk_reserve_gpu_va, LX_DXRESERVEGPUVIRTUALADDRESS); SET_IOCTL(/*0x9 */ dxgk_query_adapter_info, LX_DXQUERYADAPTERINFO); SET_IOCTL(/*0xa */ dxgk_query_vidmem_info, LX_DXQUERYVIDEOMEMORYINFO); SET_IOCTL(/*0xb */ dxgk_make_resident, LX_DXMAKERESIDENT); SET_IOCTL(/*0xc */ dxgk_map_gpu_va, LX_DXMAPGPUVIRTUALADDRESS); SET_IOCTL(/*0xd */ dxgk_escape, LX_DXESCAPE); SET_IOCTL(/*0xe */ dxgk_get_device_state, LX_DXGETDEVICESTATE); SET_IOCTL(/*0xf */ dxgk_submit_command, LX_DXSUBMITCOMMAND); SET_IOCTL(/*0x10 */ dxgk_create_sync_object, LX_DXCREATESYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x11 */ dxgk_signal_sync_object, LX_DXSIGNALSYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x12 */ dxgk_wait_sync_object, LX_DXWAITFORSYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x13 */ dxgk_destroy_allocation, LX_DXDESTROYALLOCATION2); SET_IOCTL(/*0x14 */ dxgk_enum_adapters, LX_DXENUMADAPTERS2); SET_IOCTL(/*0x15 */ dxgk_close_adapter, LX_DXCLOSEADAPTER); SET_IOCTL(/*0x16 */ dxgk_change_vidmem_reservation, LX_DXCHANGEVIDEOMEMORYRESERVATION); SET_IOCTL(/*0x17 */ dxgk_create_hwcontext, LX_DXCREATEHWCONTEXT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x18 */ dxgk_create_hwqueue, LX_DXCREATEHWQUEUE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x19 */ dxgk_destroy_device, LX_DXDESTROYDEVICE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x1a */ dxgk_destroy_hwcontext, LX_DXDESTROYHWCONTEXT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x1b */ dxgk_destroy_hwqueue, LX_DXDESTROYHWQUEUE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x1c */ dxgk_destroy_paging_queue, LX_DXDESTROYPAGINGQUEUE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x1d */ dxgk_destroy_sync_object, LX_DXDESTROYSYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x1e */ dxgk_evict, LX_DXEVICT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x1f */ dxgk_flush_heap_transitions, LX_DXFLUSHHEAPTRANSITIONS); SET_IOCTL(/*0x20 */ dxgk_free_gpu_va, LX_DXFREEGPUVIRTUALADDRESS); SET_IOCTL(/*0x21 */ dxgk_get_context_process_scheduling_priority, LX_DXGETCONTEXTINPROCESSSCHEDULINGPRIORITY); SET_IOCTL(/*0x22 */ dxgk_get_context_scheduling_priority, LX_DXGETCONTEXTSCHEDULINGPRIORITY); SET_IOCTL(/*0x23 */ dxgk_get_shared_resource_adapter_luid, LX_DXGETSHAREDRESOURCEADAPTERLUID); SET_IOCTL(/*0x24 */ dxgk_invalidate_cache, LX_DXINVALIDATECACHE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x25 */ dxgk_lock2, LX_DXLOCK2); SET_IOCTL(/*0x26 */ dxgk_mark_device_as_error, LX_DXMARKDEVICEASERROR); SET_IOCTL(/*0x27 */ dxgk_offer_allocations, LX_DXOFFERALLOCATIONS); SET_IOCTL(/*0x28 */ dxgk_open_resource, LX_DXOPENRESOURCE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x29 */ dxgk_open_sync_object, LX_DXOPENSYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECT); SET_IOCTL(/*0x2a */ dxgk_query_alloc_residency, LX_DXQUERYALLOCATIONRESIDENCY); SET_IOCTL(/*0x2b */ dxgk_query_resource_info, LX_DXQUERYRESOURCEINFO); SET_IOCTL(/*0x2c */ dxgk_reclaim_allocations, LX_DXRECLAIMALLOCATIONS2); SET_IOCTL(/*0x2d */ dxgk_render, LX_DXRENDER); SET_IOCTL(/*0x2e */ dxgk_set_allocation_priority, LX_DXSETALLOCATIONPRIORITY); SET_IOCTL(/*0x2f */ dxgk_set_context_process_scheduling_priority, LX_DXSETCONTEXTINPROCESSSCHEDULINGPRIORITY); SET_IOCTL(/*0x30 */ dxgk_set_context_scheduling_priority, LX_DXSETCONTEXTSCHEDULINGPRIORITY); SET_IOCTL(/*0x31 */ dxgk_signal_sync_object_cpu, LX_DXSIGNALSYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECTFROMCPU); SET_IOCTL(/*0x32 */ dxgk_signal_sync_object_gpu, LX_DXSIGNALSYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECTFROMGPU); SET_IOCTL(/*0x33 */ dxgk_signal_sync_object_gpu2, LX_DXSIGNALSYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECTFROMGPU2); SET_IOCTL(/*0x34 */ dxgk_submit_command_to_hwqueue, LX_DXSUBMITCOMMANDTOHWQUEUE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x35 */ dxgk_submit_wait_to_hwqueue, LX_DXSUBMITWAITFORSYNCOBJECTSTOHWQUEUE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x36 */ dxgk_submit_signal_to_hwqueue, LX_DXSUBMITSIGNALSYNCOBJECTSTOHWQUEUE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x37 */ dxgk_unlock2, LX_DXUNLOCK2); SET_IOCTL(/*0x38 */ dxgk_update_alloc_property, LX_DXUPDATEALLOCPROPERTY); SET_IOCTL(/*0x39 */ dxgk_update_gpu_va, LX_DXUPDATEGPUVIRTUALADDRESS); SET_IOCTL(/*0x3a */ dxgk_wait_sync_object_cpu, LX_DXWAITFORSYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECTFROMCPU); SET_IOCTL(/*0x3b */ dxgk_wait_sync_object_gpu, LX_DXWAITFORSYNCHRONIZATIONOBJECTFROMGPU); SET_IOCTL(/*0x3c */ dxgk_get_allocation_priority, LX_DXGETALLOCATIONPRIORITY); SET_IOCTL(/*0x3d */ dxgk_query_clock_calibration, LX_DXQUERYCLOCKCALIBRATION); SET_IOCTL(/*0x3e */ dxgk_enum_adapters3, LX_DXENUMADAPTERS3); SET_IOCTL(/*0x3f */ dxgk_share_objects, LX_DXSHAREOBJECTS); SET_IOCTL(/*0x40 */ dxgk_open_sync_object_nt, LX_DXOPENSYNCOBJECTFROMNTHANDLE2); SET_IOCTL(/*0x41 */ dxgk_query_resource_info_nt, LX_DXQUERYRESOURCEINFOFROMNTHANDLE); SET_IOCTL(/*0x42 */ dxgk_open_resource_nt, LX_DXOPENRESOURCEFROMNTHANDLE); } |

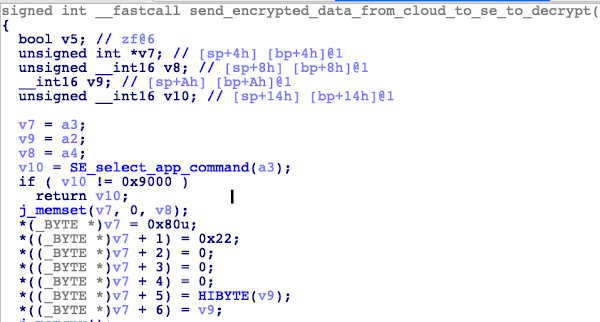

When working through this list of functions, I eventually stumbled into dxgk_signal_sync_object_cpu which has immediate red flags. We can see that data is copied from userland into kernel space via dxg_copy_from_user() in the form of the structure d3dkmt_signalsynchronizationobjectfromcpu and the data is passed as various arguments to dxgvmb_send_signal_sync_object().

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 | struct d3dkmt_signalsynchronizationobjectfromcpu { d3dkmt_handle device; uint object_count; d3dkmt_handle *objects; uint64_t *fence_values; struct d3dddicb_signalflags flags; }; static int dxgk_signal_sync_object_cpu(struct dxgprocess *process, void *__user inargs) { struct d3dkmt_signalsynchronizationobjectfromcpu args; struct dxgdevice *device = NULL; struct dxgadapter *adapter = NULL; int ret = 0; TRACE_FUNC_ENTER(__func__); ret = dxg_copy_from_user(&args, inargs, sizeof(args)); // User controlled data copied into args if (ret) goto cleanup; device = dxgprocess_device_by_handle(process, args.device); if (device == NULL) { ret = STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER; goto cleanup; } adapter = device->adapter; ret = dxgadapter_acquire_lock_shared(adapter); if (ret) { adapter = NULL; goto cleanup; } ret = dxgvmb_send_signal_sync_object(process, &adapter->channel, // User controlled data passed as arguments args.flags, 0, 0, // specific interest args.object_count args.object_count, args.objects, 0, NULL, args.object_count, args.fence_values, NULL, args.device); cleanup: if (adapter) dxgadapter_release_lock_shared(adapter); if (device) dxgdevice_release_reference(device); TRACE_FUNC_EXIT(__func__, ret); return ret; } |

The IOCTL handler dxgk_signal_sync_object_cpu lacked input validation of user-controlled data. The user passes a d3dkmt_signalsynchronizationobjectfromcpu structure which contains a uint value for object_count. Moving deeper into the code, in dxgvmb_send_signal_sync_object (drivers/gpu/dxgkrnl/dxgvmbus.c), we know that we control the following arguments at this moment and there’s been zero validation:

- args.flags (flags)

- args.object_count (object_count, fence_count)

- args.objects (objects)

- args.fence_values (fences)

- args.device (device)

An interesting note is that args.object_count is being used for both the object_count and fence_count. Generally a count is used to calculate length, so it’s important to keep an eye out for counts that you control. You’re about to witness some extremely trivial bugs. If you’re inexperienced at auditing C code for vulnerabilities, see how many issues you can spot before reading the explanations below.

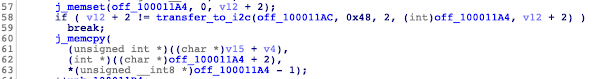

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 | int dxgvmb_send_signal_sync_object(struct dxgprocess *process, struct dxgvmbuschannel *channel, struct d3dddicb_signalflags flags, uint64_t legacy_fence_value, d3dkmt_handle context, uint object_count, d3dkmt_handle __user *objects, uint context_count, d3dkmt_handle __user *contexts, uint fence_count, uint64_t __user *fences, struct eventfd_ctx *cpu_event_handle, d3dkmt_handle device) { int ret = 0; struct dxgkvmb_command_signalsyncobject *command = NULL; uint object_size = object_count * sizeof(d3dkmt_handle); uint context_size = context_count * sizeof(d3dkmt_handle); uint fence_size = fences ? fence_count * sizeof(uint64_t) : 0; uint8_t *current_pos; uint cmd_size = sizeof(struct dxgkvmb_command_signalsyncobject) + object_size + context_size + fence_size; if (context) cmd_size += sizeof(d3dkmt_handle); command = dxgmem_alloc(process, DXGMEM_VMBUS, cmd_size); if (command == NULL) { ret = STATUS_NO_MEMORY; goto cleanup; } command_vgpu_to_host_init2(&command->hdr, DXGK_VMBCOMMAND_SIGNALSYNCOBJECT, process->host_handle); if (flags.enqueue_cpu_event) command->cpu_event_handle = (winhandle) cpu_event_handle; else command->device = device; command->flags = flags; command->fence_value = legacy_fence_value; command->object_count = object_count; command->context_count = context_count; current_pos = (uint8_t *) &command[1]; ret = dxg_copy_from_user(current_pos, objects, object_size); if (ret) { pr_err("Failed to read objects %p %d", objects, object_size); goto cleanup; } current_pos += object_size; if (context) { command->context_count++; *(d3dkmt_handle *) current_pos = context; current_pos += sizeof(d3dkmt_handle); } if (context_size) { ret = dxg_copy_from_user(current_pos, contexts, context_size); if (ret) { pr_err("Failed to read contexts %p %d", contexts, context_size); goto cleanup; } current_pos += context_size; } if (fence_size) { ret = dxg_copy_from_user(current_pos, fences, fence_size); if (ret) { pr_err("Failed to read fences %p %d", fences, fence_size); goto cleanup; } } ret = dxgvmb_send_sync_msg_ntstatus(channel, command, cmd_size); cleanup: if (command) dxgmem_free(process, DXGMEM_VMBUS, command); TRACE_FUNC_EXIT_ERR(__func__, ret); return ret; } |

This count that we control is used in multiple locations throughout the IOCTL for buffer length calculations without validation. This leads to multiple integer overflows, followed by an allocation that is too short which causes memory corruption.

Integer overflows:

17) Our controlled value object_count is used to calculate object_size

19) Our controlled value fence_count is used to calculate fence_size

21) The final result of cmd_size is calculated using the previous object_size and fence_size values

25) cmd_size could simply overflow from adding the size of d3dkmt_handle if it were large enough

Memory corruption:

27) The result of cmd_size is ultimately used as a length calculation for dxgmem_alloc. As an attacker, we can force this to be very small.

Since our new allocated buffer command can be extremely small, the following execution that writes to it could cause memory corruption.

33-44) These are all writing data to what is pointing at the buffer, and depending on the size we force there’s no guarantee that there is space for the data.

46,59) Eventually execution will lead to two different calls of dxg_copy_from_user. In both cases, it is copying in user-controlled data using the original extremely large size values (remember our object_count was used to calculate both object_size and fence_size).

Hopefully this inspired you to take a peek at other opensource drivers and hunt down security bugs. This issue was reported to MSRC on May 20th, 2020 and resolved on August 26th, 2020 after receiving the severity of Important with an impact of Elevation of Privilege.

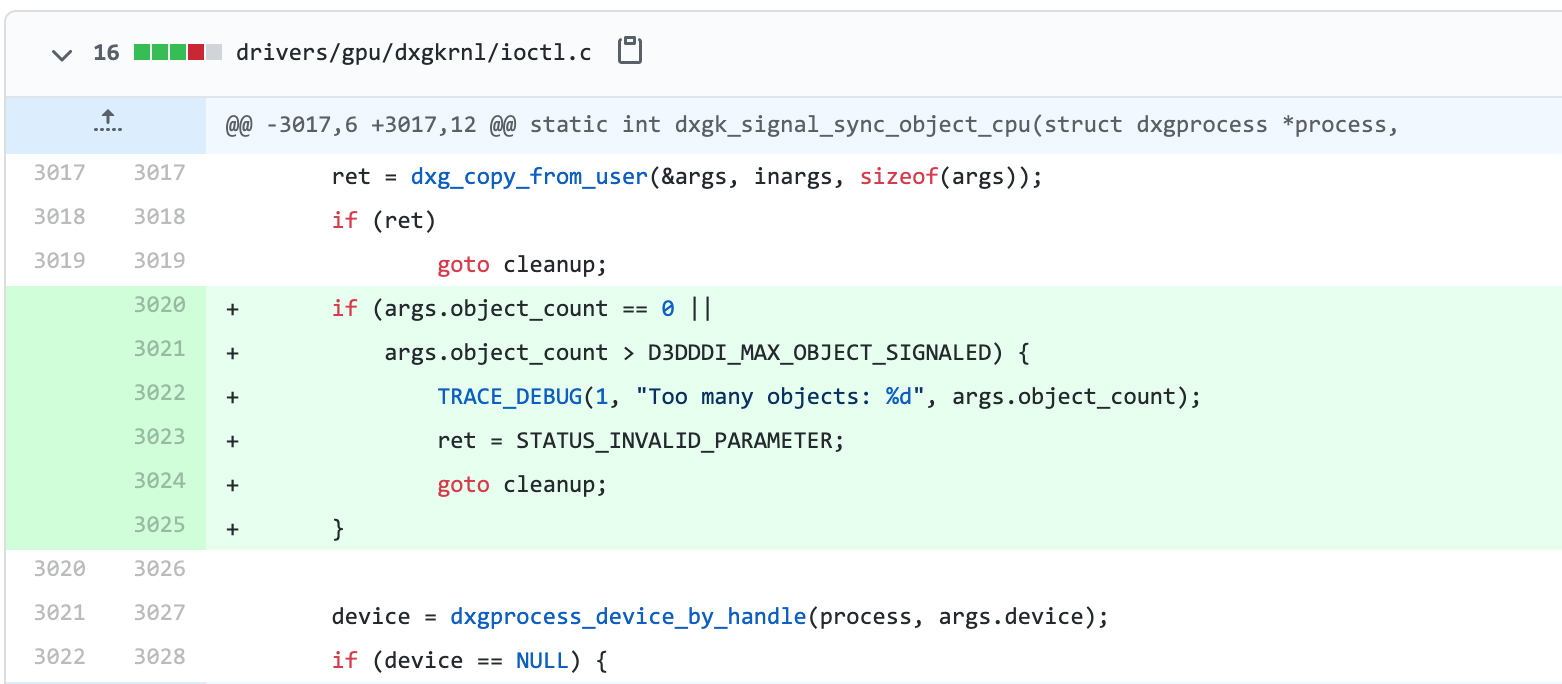

You can view the patch commit here with the new added validation.