[1]

[1]I watched the TV show Homeland for the first time a few months ago. This particular episode had a plot twist that involved a terrorist remotely hacking into the pacemaker of the Vice President of the United States.

People follow this show religiously, and there were articles questioning the plausibility of the pacemaker hack. Physicians were questioned as to the validity of the hack and were quoted saying that this is not possible in the real world [2].

In my professional opinion, the episode was not too far off the mark.

In the episode, a terrorist finds out that the Vice President has a bad heart and his pacemaker can be remotely accessed with the correct serial number. The terrorist convinces a congressman to retrieve the serial number, and then his hacker accomplice uses the serial to remotely interrogate the pacemaker. Once the hacker has connected to the pacemaker, he instructs the implantable device to deliver a lethal jolt of electricity. The Vice President keels over, clutches his chest, and dies.

My first thought after watching this episode was “TV is so ridiculous! You don’t need a serial number!”

In all seriousness, the episode really wasn’t too implausible. Let’s dissect the Hollywood pacemaker hack and see how close to reality they were. First, some background on the implantable medical technology:

The two most common implantable devices for treating cardiac conditions are the ““`pacemaker and the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

The primary function of the pacemaker is to monitor the heart rhythm of a patient and to ensure that the heart is beating regularly. If the pacemaker detects certain arrhythmia (an irregular heartbeat or abnormal heart rhythm), the pacemaker sends a low voltage pulse to the heart to resynchronize the electrical rhythm. A pacemaker does not have the capability to deliver a high voltage electrical shock.

Newer model ICD’s not only have pacing functionality, but they are also able to deliver a high voltage shock to the heart. The ICD most commonly detects an arrhythmia known as ventricular fibrillation (VF), which is a condition that causes irregular contractions of the cardiac muscle. VF is the most common arrhythmia associated with sudden cardiac death. When an ICD detects VF, it will deliver a shock to the heart in an attempt to reverse the condition.

Back to Homeland, let’s see how close Hollywood was to getting it right. Although they mention a pacemaker in the episode, the actual implantable device is an ICD.

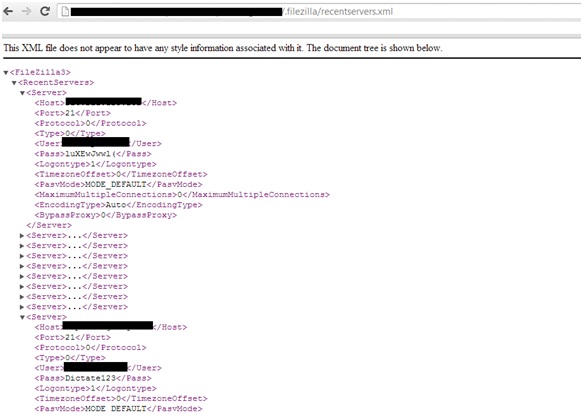

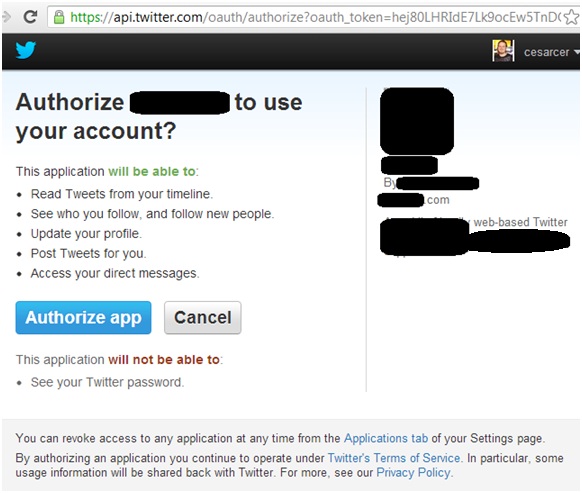

HOMELAND: The congressman is told to retrieve the serial number from a plastic box in the Vice President’s office. The plastic box he retrieves the serial number from has a circular wand and telephone inputs on the side.

Fact! The plastic box on the episode is a commonly used remote monitor/bedside transmitter. The primary use of the bedside transmitter is to read patient data from the pacemaker or ICD and send the data to a physician over the telephone line or network connection. The benefit to this technology is reduced in-person visits to the physician’s clinic. The data can be analyzed remotely, and the physician can determine whether an in-person visit is required.

Before 2006, all pacemaker programming and interrogation was performed using inductive telemetry. Programming using inductive telemetry requires very close skin contact. The programming wand is held up to the chest, a magnetic reed switch is opened on the implant, and the device is then open for programming and/or interrogation. Communication is near field (sub 1MHZ), and data rates are less than 50KHZ.

The obvious drawback to inductive telemetry is the extremely close range required. To remedy this, manufacturers began implementing radiofrequency (RF) communication on their devices and utilized the MICS (Medical Implant Communication Service) frequency band. MICS operates in the 402-405MHZ band and offers interrogation and programming from greater distances, with faster transfer speeds. In 2006, the FDA began approving fully wireless-5based pacemakers and ICDs.

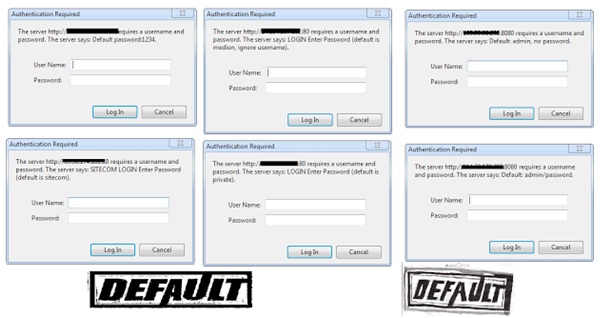

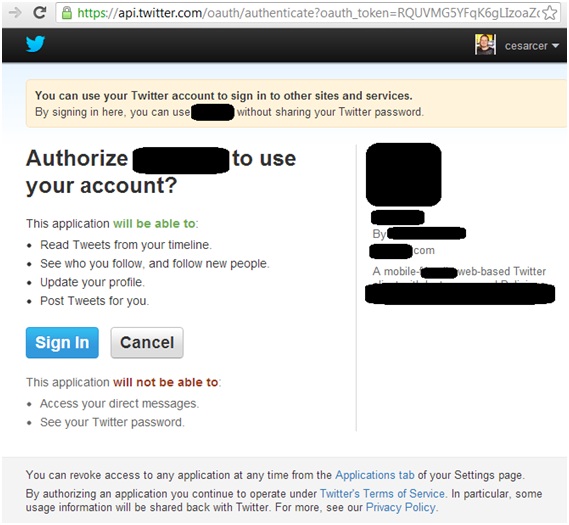

Recent remote monitors/bedside transmitters and pacemaker/ICD programmers support both inductive telemetry as well as RF communication. When communicating with RF implantable devices, the devices typically pair with the programmer or transmitter by using the serial number, or the serial number and model number. It’s important to note that currently the bedside transmitters do not allow a physician to dial into the devices and reprogram the devices. The transmitter can only dial out.

So far, so good.

HOMELAND: The hacker receives the serial number on his cell phone and uses his laptop to remotely connect to the ICD. The laptop screen displays real-time electrocardiogram (ECG) readouts, heart beats-per-minute, and waveforms generated by the ICD. He then instructs his software to deliver defibrillation. Then it’s game over for the victim at the other end.

If you look past the usual bells and whistles that are standard issue with exploit software on TV, the scrolling hex dumps, the c code in the background—the waveform and beats per minute (BPM) diagnostic data from the implant that is shown in real-time is legitimate and can be retrieved over the implant’s wireless interface. The official pacemaker/ICD programmers used by the physicians have a similar interface. In the case of ICDs, the pacing and high voltage leads are all monitored, and the waveforms can be displayed in real time.

The attacker types in a command to remotely induce defibrillation on the victim’s ICD.It is possible to remotely deliver shocks to ICDs. The functionality exists for testing purposes. Depending on the device model and manufacturer, it is possible to deliver a jolt in excess of 800 volts.

Moving on to the remote attack itself, the TV episode never mentioned where the attacker was located, and even if it was possible to dial into the remote monitor, it was disconnected.

Some manufacturers have tweaked the MICS standard to allow communication from greater distances and to allow communication over different frequencies. Let’s talk a little about how these devices communicate, using a fairly new model ICD as an example.

The Wake-up Scheme:

Before an implantable device can be reprogrammed, it must be “woken up”. Battery conservation is extremely important. When the battery has been depleted, surgery is required to replace the device. To conserve power, the implants continually run in a low power mode, until they receive an encoded wake-up message. The transceiver in this ICD supports wake-up over the 400MHZ MICS band, as well as 2.45GHZ.

To wake-up and pair with an individual device, you must transmit the serial and model number in the request. Once a device has paired with the correct model and serial number and you understand the communications protocol, you essentially have full control over the device. You can read and write to memory, rewrite firmware, modify pacemaker/ICD parameters, deliver shocks, and so on.

When using a development board that uses the same transceiver, with no modifications to the stock antenna, reliable communication will max out at about 50 feet. With a high gain antenna, you could probably increase this range.

Going back to Homeland, the only implausible aspect of the hack was the range in which the attack was carried out. The attacker would have had to be in the same building or have a transmitter set up closer to the target. With that said, the scenario was not too far-fetched. The technology as it stands could very easily be adapted for physicians to remotely adjust parameters and settings on these devices via the bedside transmitters. In the future, a scenario like this could certainly become a reality.

––

As there are only a handful of people publicizing security research on medical devices, I was curious to know where the inspiration for this episode came from. I found an interview with the creators of the show where the interviewer asked where the idea for the plot twist came from [3]. The creators said the inspiration for the episode was from an article in the New York Times, where a group of researchers had been able to cause an ICD to deliver jolts of electricity [4].

This work was performed by Kevin Fu and researchers at the University Of Massachusetts in 2008. Kevin is considered a pioneer in the field of medical device security. The paper he and the other researchers released (“Pacemakers and Implantable Cardiac Defibrillators: Software Radio Attacks and Zero-Power Defenses”) [5] is a good read and was my initial inspiration for moving into this field.

I recommend reading the paper, but I will briefly summarize their ICD attack. Their paper dates back to 2008. At the time, the long range RF-based implantable devices were not as common as they are today. The device they used for testing has a magnetic reed switch, which needs to be opened to allow reprogramming. They initiated a wakeup by placing a magnet in close proximity to the device, which activated the reed switch. Then they captured an ICD shock sequence from an official ICD/pacemaker programmer and replayed that data using a software radio.

The obvious drawback was the close proximity required to carry out a successful attack. In this case, they were restricted by the technology available at the time.

At IOActive, I’ve been spending the majority of my time researching RF-based implants. We have created software for research purposes that will wirelessly scan for new model ICDs and pacemakers without the need for a serial or model number. The software then allows one to rewrite the firmware on the devices, modify settings and parameters, and in the case of ICDs, deliver high-voltage shocks remotely.

At IOActive, this research has a personal attachment. Our CEO Jennifer Steffens’ father has a pacemaker. He has had to undergo multiple surgeries due to complications with his implantable device.

Our goal with this research is not for people to lose faith in these life-saving devices. These devices DO save lives. We are also extremely careful when demonstrating these threats to not release details that could allow an attack to be easily reproduced in the wild.

Although the threat of a malicious attack to anyone with an implantable device is slim, we want to mitigate these risks no matter how minor. We are actively engaging medical device manufacturers and sharing our knowledge with them.