Introduction

In our previous post on platform security (see here) we provided a brief introduction into platform security protections on AMD-based platforms and touched upon the topic of AMD Platform Secure Boot (PSB).

As a quick reminder, the purpose of PSB is to provide a hardware root-of-trust that will verify the integrity of the initial UEFI firmware phases, thereby preventing persistent firmware implants.

In this part of the blog series, we will dig deeper into the nitty gritty details of PSB, including a first glimpse of how it works under the hood, how it should be configured and, naturally, how various major vendors fail to do so.

Architecture

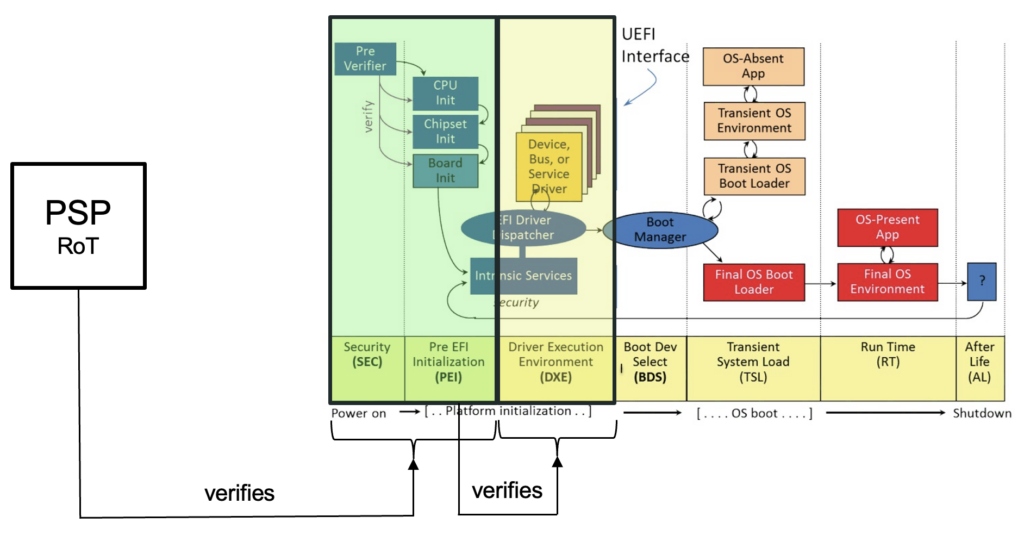

To begin, it is important to understand that the UEFI boot process is divided into various phases, referred to as SEC, PEI, DXE, BDS, TSL, RT and AL. For the sake of brevity, we won’t go into detail on the purpose of each phase as it has already been widely covered already (e.g. here).

In short, the role of the PSB is to ensure that the initial UEFI phases, specifically the SEC and PEI phase, are properly verified and cannot be tampered with. In turn, the PEI phase will verify the DXE phase using a proprietary and vendor-specific method.

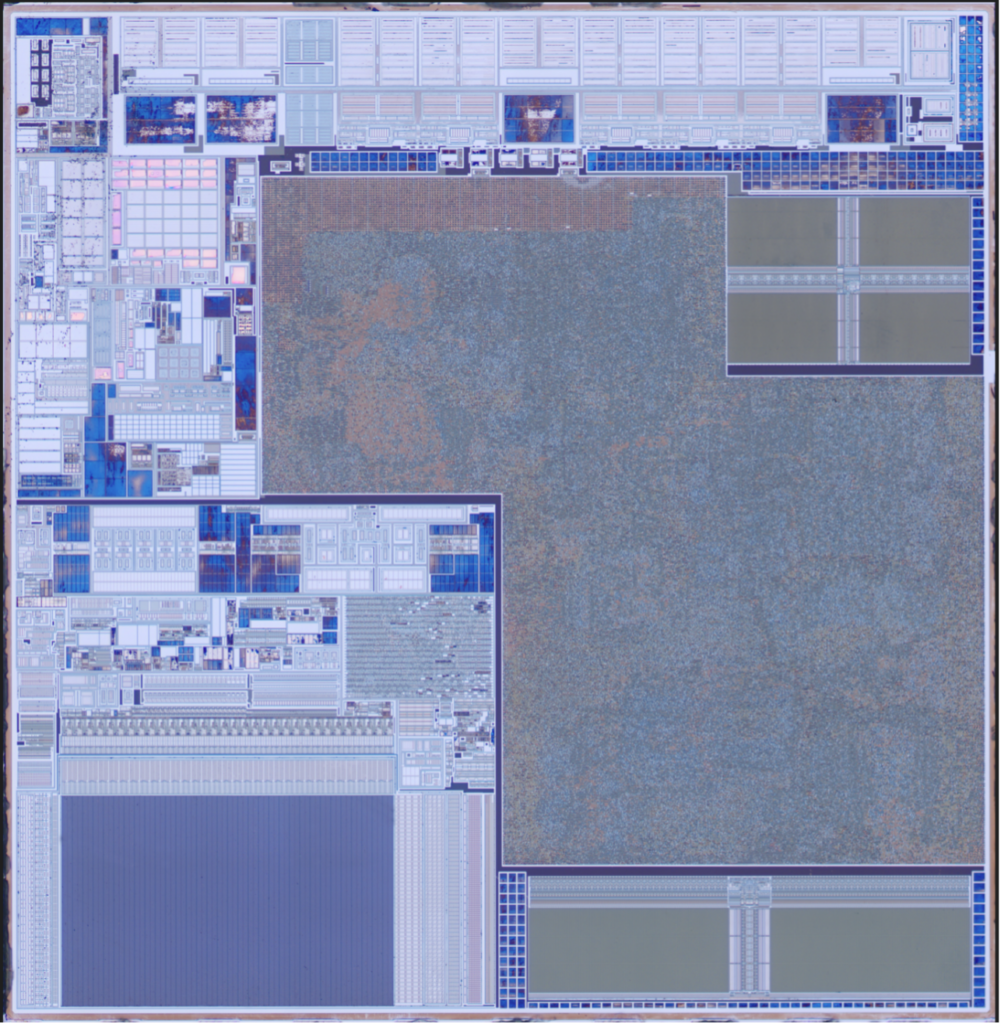

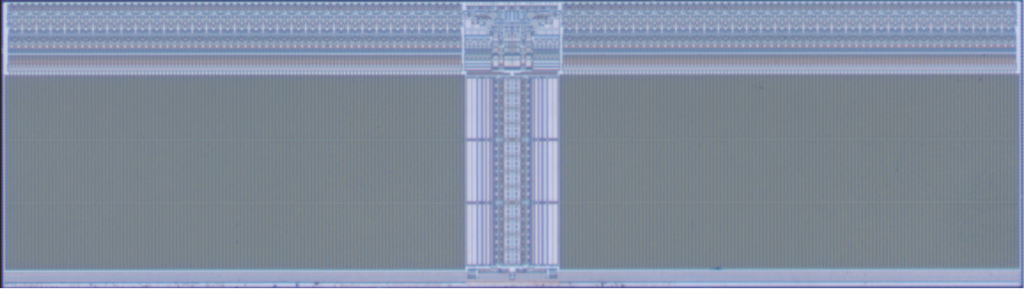

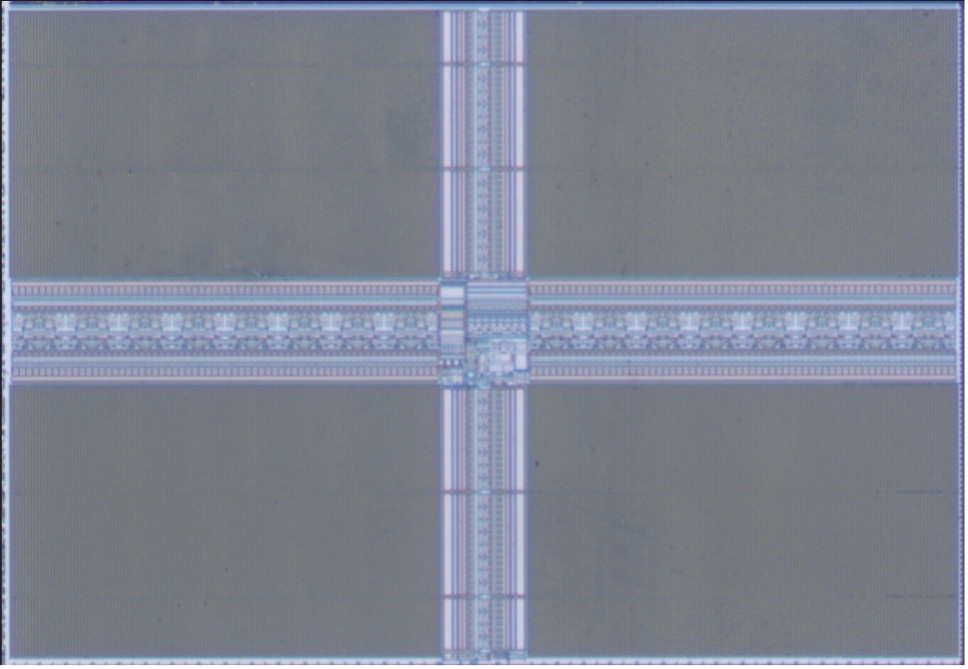

The resulting scheme is summarized in the following image:

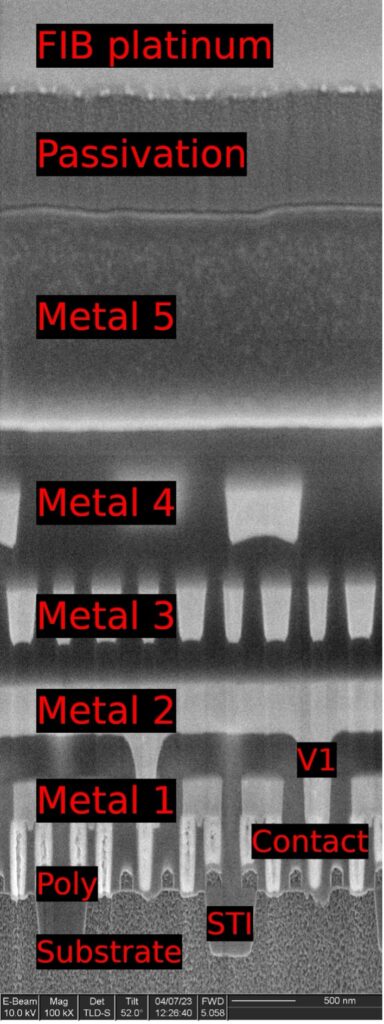

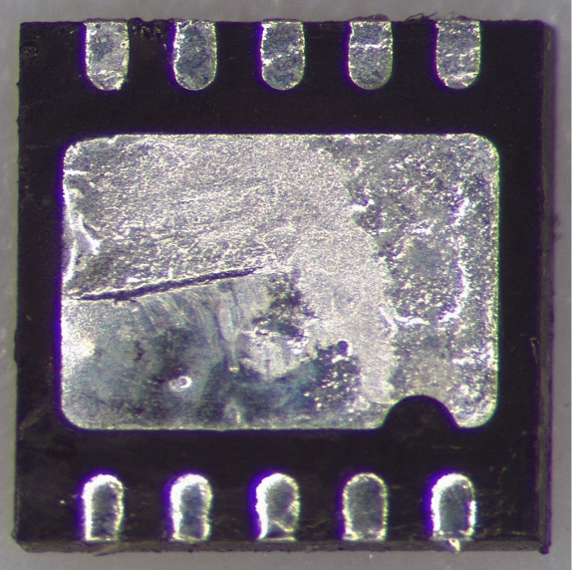

Upon reset, only the AMD Platform Security Processor (PSP), an ARM-based co-processor embedded within the AMD chip, is running. It functions as a hardware root-of-trust and verifies the SEC and PEI phase portions of the UEFI firmware. If verification succeeds, then it releases the main cores that then start executing the SEC and PEI phase.

Trust Hierarchy

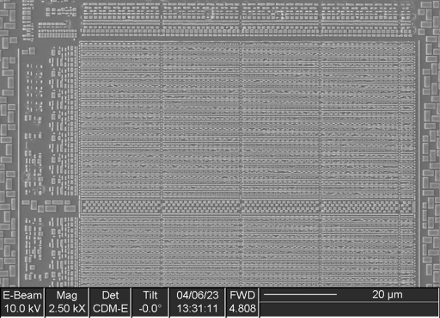

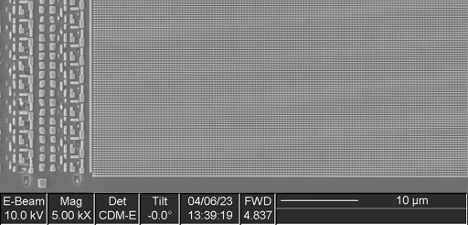

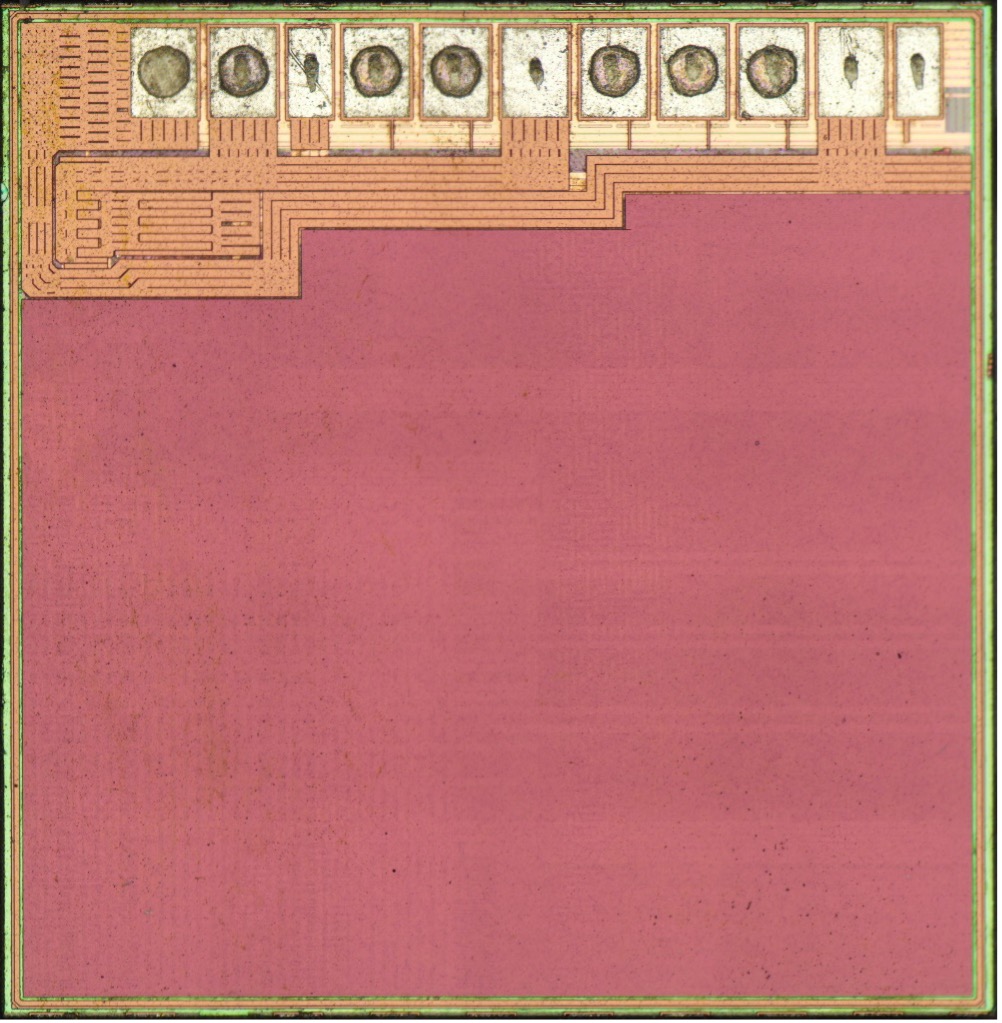

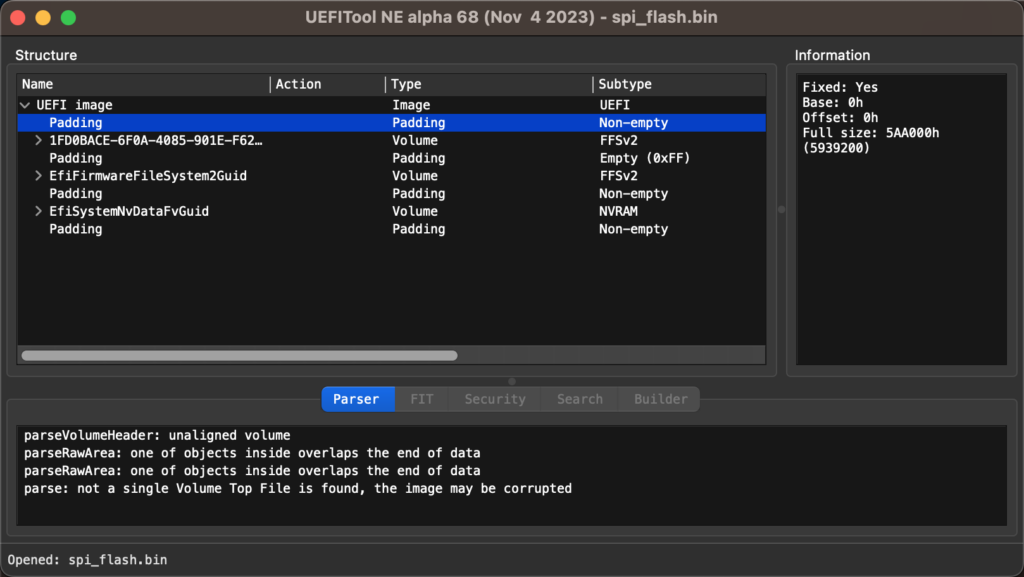

In order to understand the trust hierarchy in more depth, we will first take a look at how the UEFI firmware, stored in the SPI flash, is structured. To do so, we will use the SPI flash dump we have obtained from an AMD-based Huawei Matebook 16 (BIOS v2.28).

When we open up a SPI flash dump with our trusty UEFI Tool, we will typically see, among others, the following structures:

- Padding areas

- Firmware volumes (containing DXE drivers and SMM modules)

- NVRAM data (containing non-volatile configuration data, i.e. UEFI variables)

However, while UEFI Tool correctly identifies firmware volumes that contain code executed in the DXE phase of the UEFI boot process, the code running in the SEC and PEI phases seems to be missing altogether.

This is because it does not support parsing an AMD platform specific structure called the Embedded Firmware Structure (EFS). Once again, for the sake of brevity, as the structure is relatively complex, we will only focus on portions relevant to the chain-of-trust.

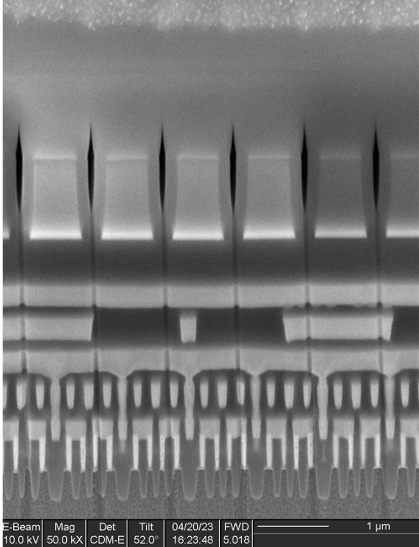

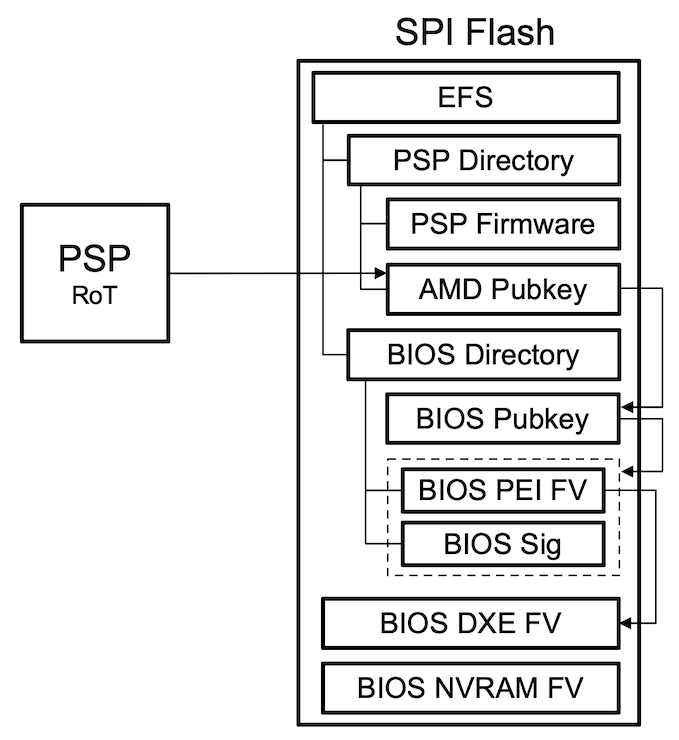

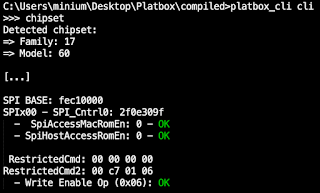

As described here, the EFS is located at one of the pre-defined locations in the SPI flash and contains pointers to:

- The PSP directory table that includes:

- The BIOS signing key (entry type 0x05)

- The BIOS PEI firmware volume (entry type 0x62)

- The BIOS PEI firmware volume signature (entry type 0x07)

- The BIOS directory table that includes:

- The AMD root signing key (entry type 0x00)

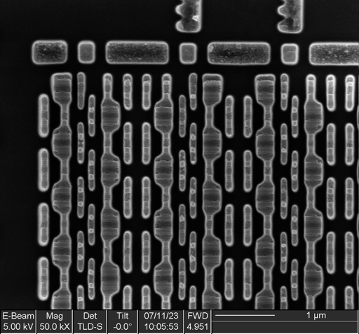

In visualized form, the resulting data structure looks as follows:

As a sidenote, we have also developed a simple parser (available here) that can be used to parse and extract the different portions of the PSP and BIOS directories.

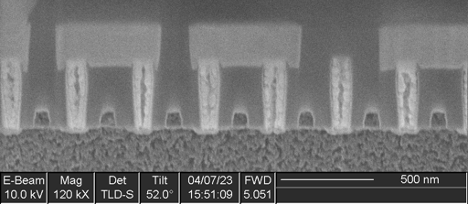

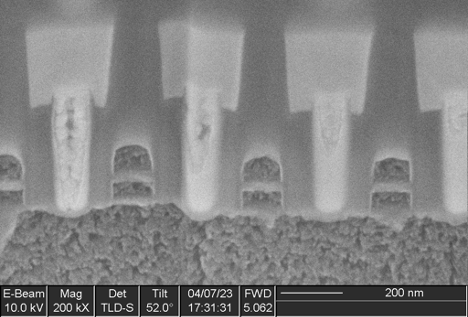

Upon reset, the PSP will hold the main cores and verify the trust chain in the following order:

- The AMD root signing key is verified against a SHA256 hash programmed into the PSP

- The BIOS signing key is verified against the AMD root signing key

- The BIOS PEI firmware volume is verified against the BIOS signing key

At this point the PSP releases the main cores and the SEC+PEI phase code, stored in the PEI firmware volume, will execute. Then, to complete the chain-of-trust, a vendor-specific PEI module will verify the DXE firmware volume(s).

PSB Configuration

The next step is to understand how we can interact with the PSP to determine whether the PSB is properly configured or not. This, in turn, could be used to implement a simple tool to detect potential misconfigurations.

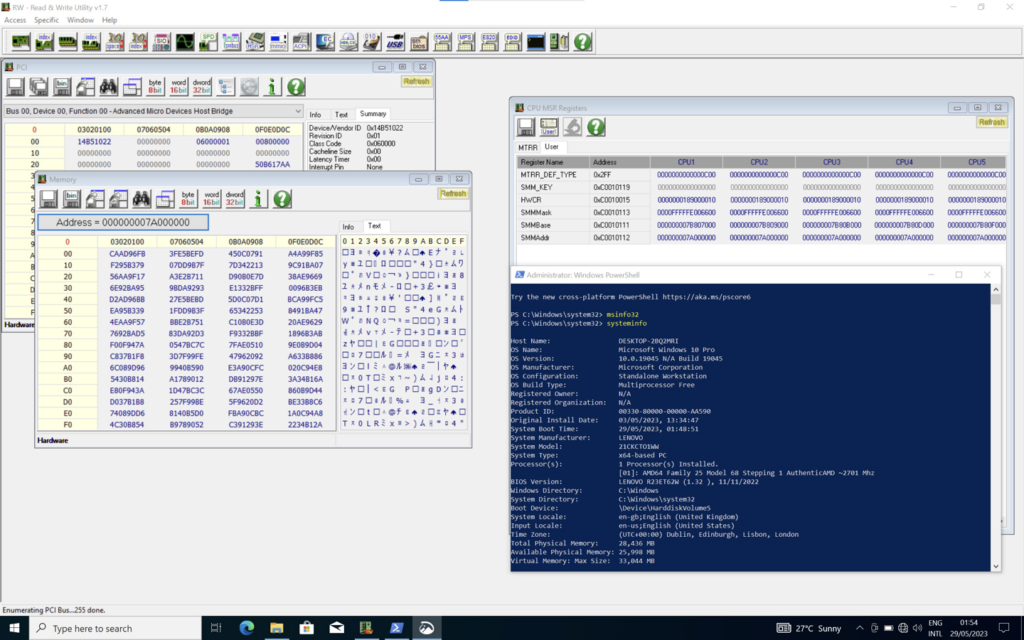

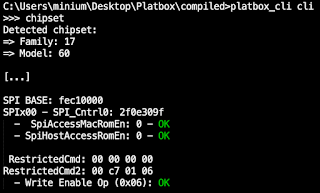

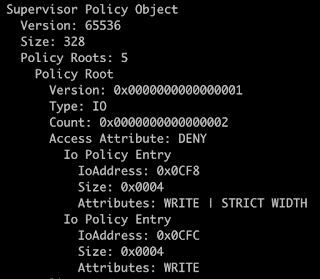

Here we found that the configuration can be checked by first determining the PSP MMIO base address and then, at a specific offset, reading out the value of two PSB-related registers.

PSP MMIO Base Address

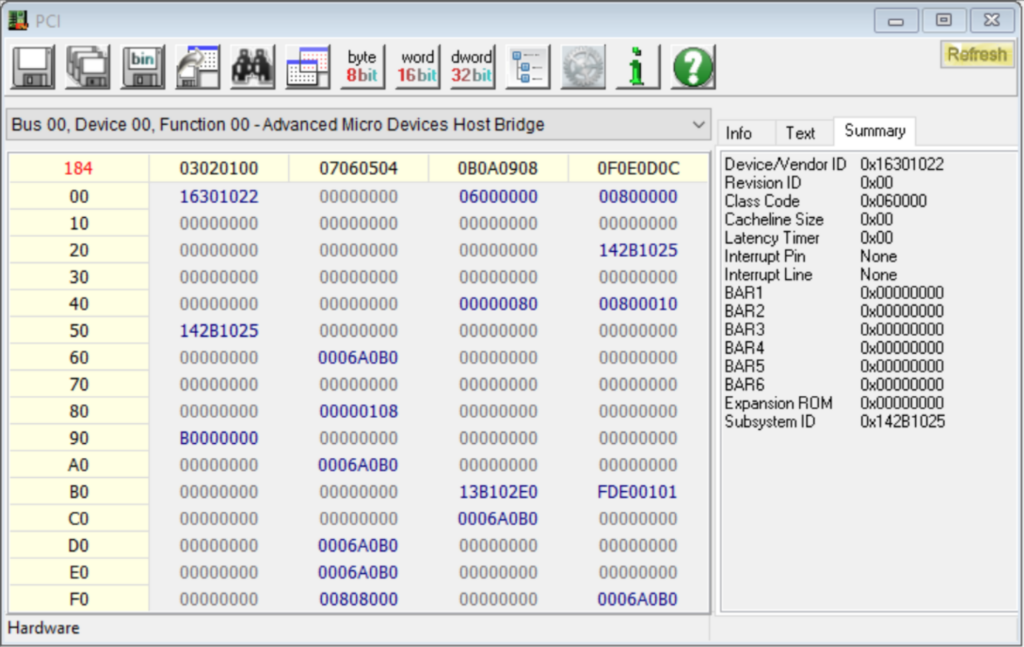

First, the PSP MMIO base address is obtained by writing a specific value to a register of the AMD IOHUB Core (IOHC). More specifically:

- 0x13E102E0 for families 17h, model 30h/70h or family 19h, model 20h or

- 0x13B102E0 for all other models

is written to the register at offset 0xB8 of the IOHC device (on bus 00h, device 00h, function 00h) and the result is read from the register at offset 0xBC.

For example, on an Acer Swift 3 (fam 17h, model 60h) we write the value 0x13B102E0 at offset 0xB8 of the IOHC and read the base address 0xFDE00000 (after masking) at offset 0xBC.

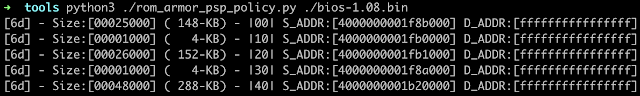

PSB Configuration Registers

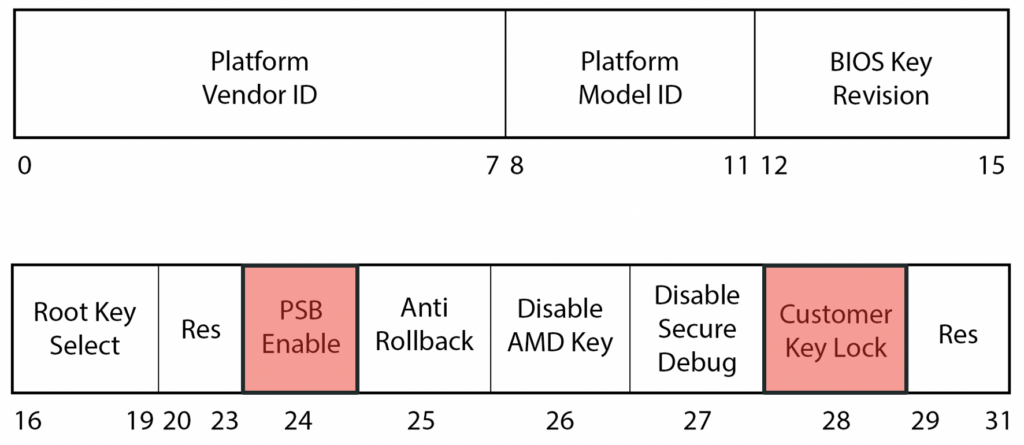

The PSB fuse register, located at offset 0x10994, reflects the actual fuse configuration and has the following structure:

It has various fields, such as:

- the platform vendor ID and platform model ID to uniquely identify the platform

- the BIOS key revision and anti-rollback to revoke BIOS signing keys

- the AMD disable key to prevent booting a BIOS signed with the AMD root signing key

- the PSB enable field to enable the feature

- the customer key lock to permanently burn the fuses

We observed that on systems with the PSB enabled, typically the platform vendor ID, the platform model ID, the PSB enable bit and the customer key lock are configured accordingly. In fact, if the BIOS was compiled with the feature enabled, the fusing process occurs automatically when the system boots for the first time.

Interestingly, the PSB can also be permanently disabled by setting the PSB enable bit to 0 and the customer key lock to 1. This would enable an attacker to leave the system vulnerable indefinitely and is similar to what was discovered for Intel BootGuard by Alexander Ermolov (see Safeguarding Rootkits: Intel BootGuard at ZeroNights).

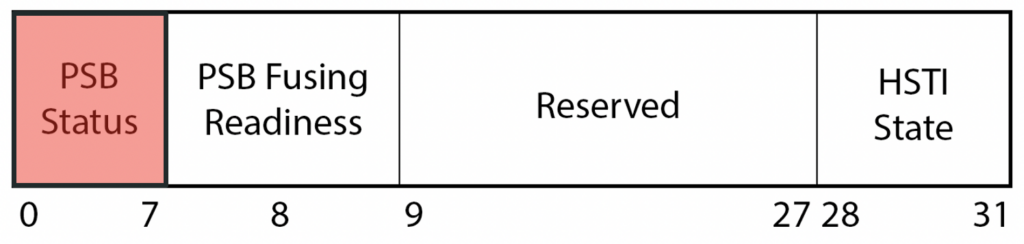

The PSB status register, located at offset 0x10998, is used for obtaining PSB state information and has the following structure:

Here we only know that the PSB status field returns 0x00 if no errors occurred; otherwise returns a non-zero value likely corresponding to a specific error code.

Vulnerabilities

Now that we understand how the PSB should be configured, we would like to walk you through misconfiguration and implementation issues we discovered during our research.

For completeness, the list of systems we tested and whether they were found to be vulnerable or not can be found in a table at the end of this blog.

Configuration flaws

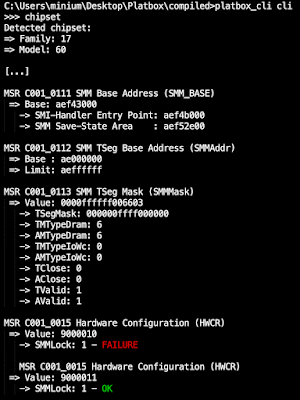

Based on our knowledge of the PSB fuse and status registers, we implemented the logic into our in-house developed platform testing tool Platbox (see here) and discovered that almost none of the tested systems had the feature enabled.

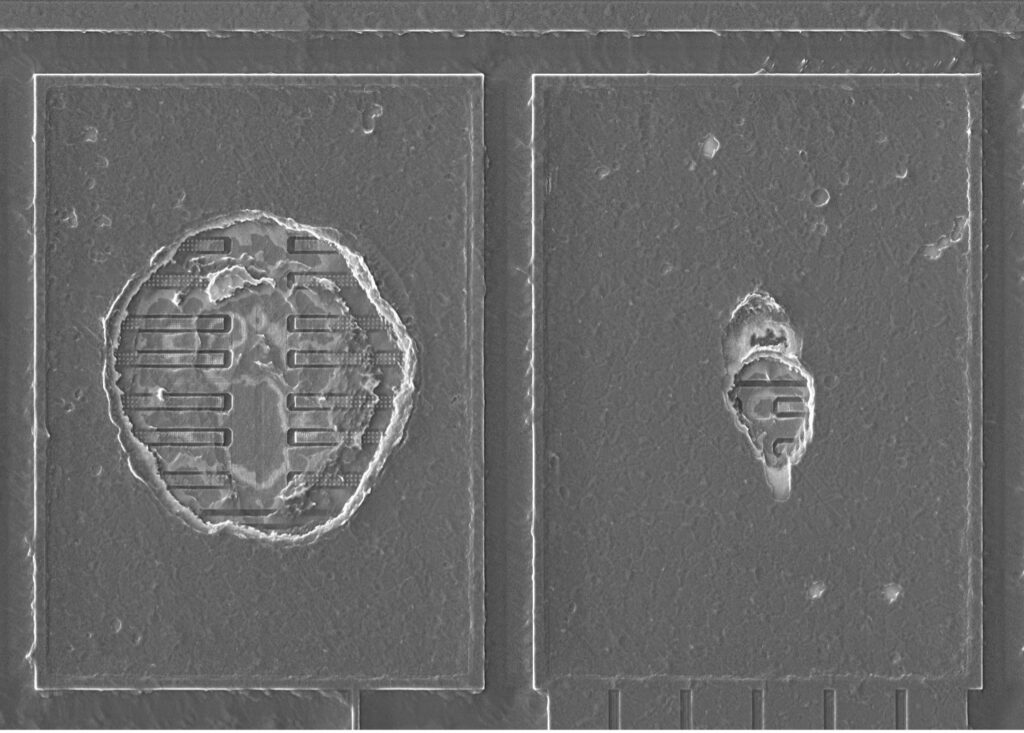

As can be seen below, the Lenovo IdeaPad 1 Gen7 (BIOS JTCN44WW) did not have the PSB fuse register burned and the PSB status field returned a non-zero value. In fact, the same pattern was observed on all other vulnerable systems.

When trying to determine the root cause, we found that various data structures that are essential to the correct functioning of the PSB were missing, such as the BIOS signing key and the BIOS PEI firmware volume signature. This may indicate that already during the build process of the firmware image the feature was simply disabled.

Implementation flaws

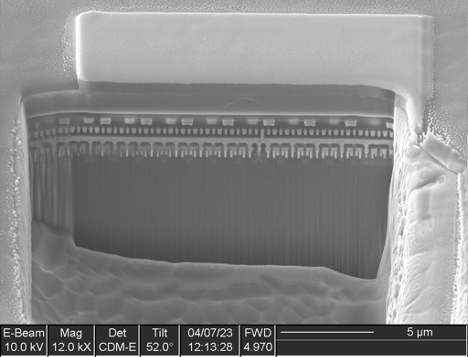

Beyond configuration flaws, we also wanted to find out whether there were any potential implementation issues. While AMD implements the first portion of the chain-of-trust, verifying the SEC and PEI phase, we decided to focus on the vendor-specific portion that verifies the DXE phase.

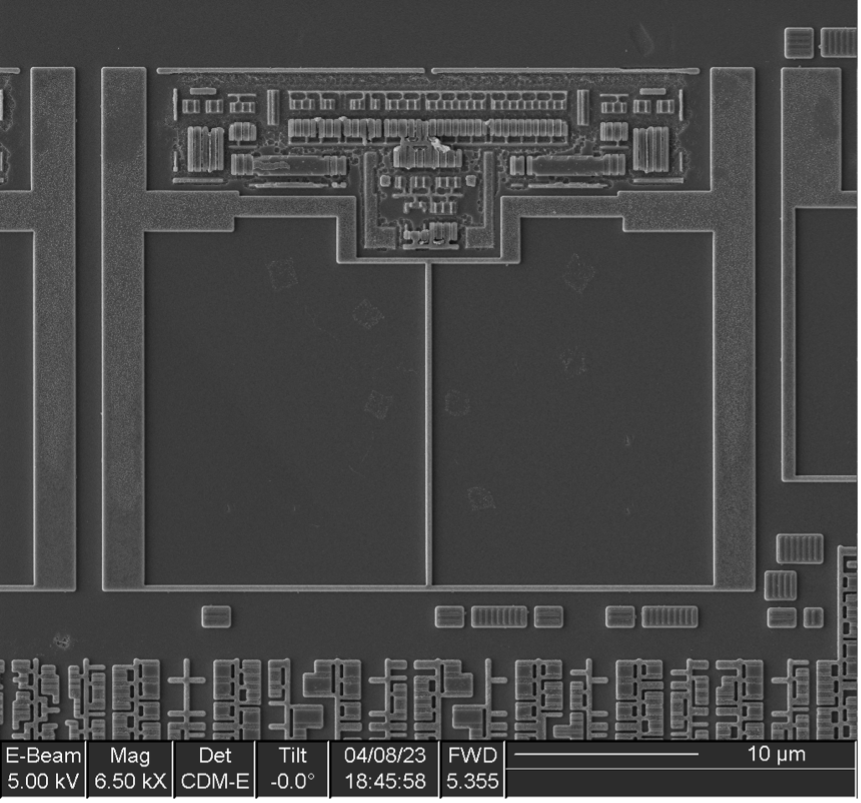

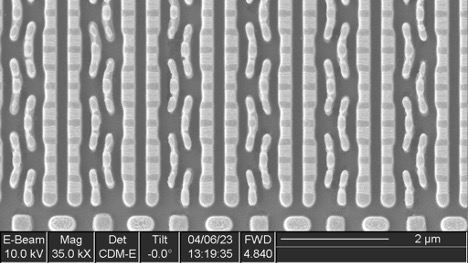

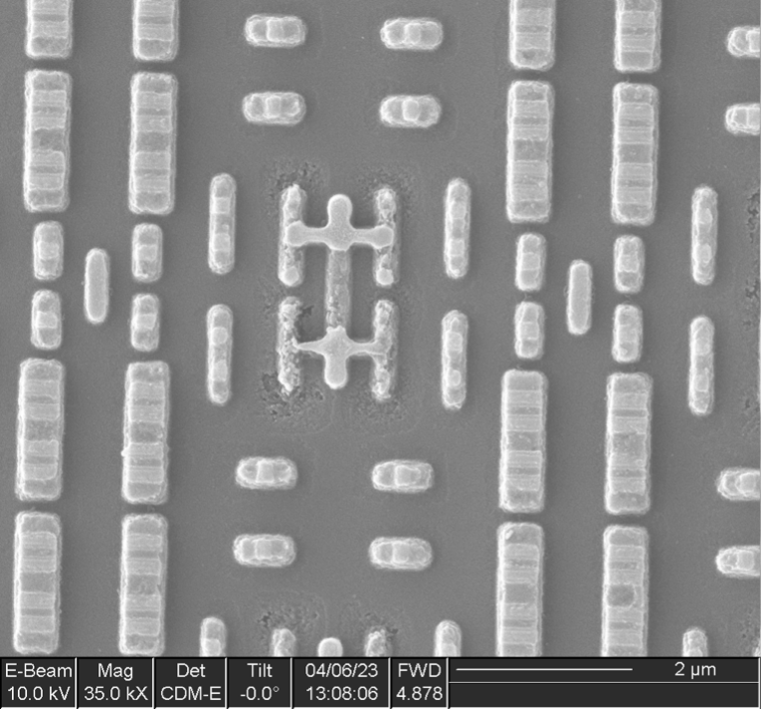

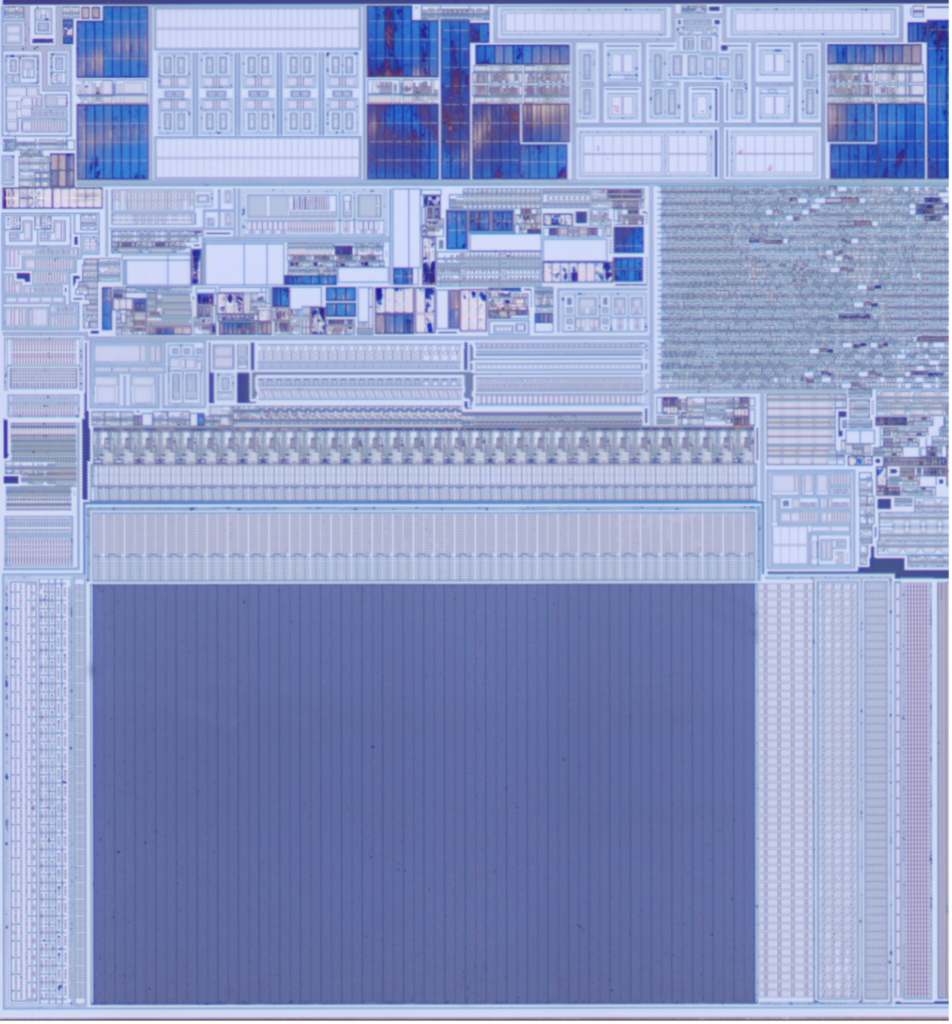

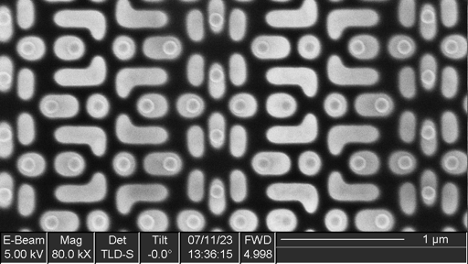

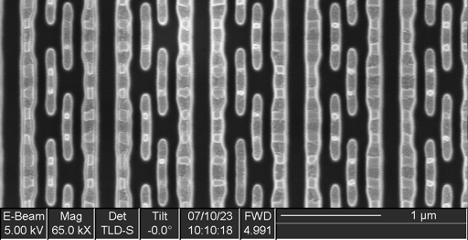

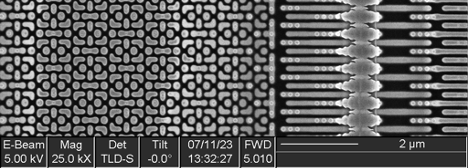

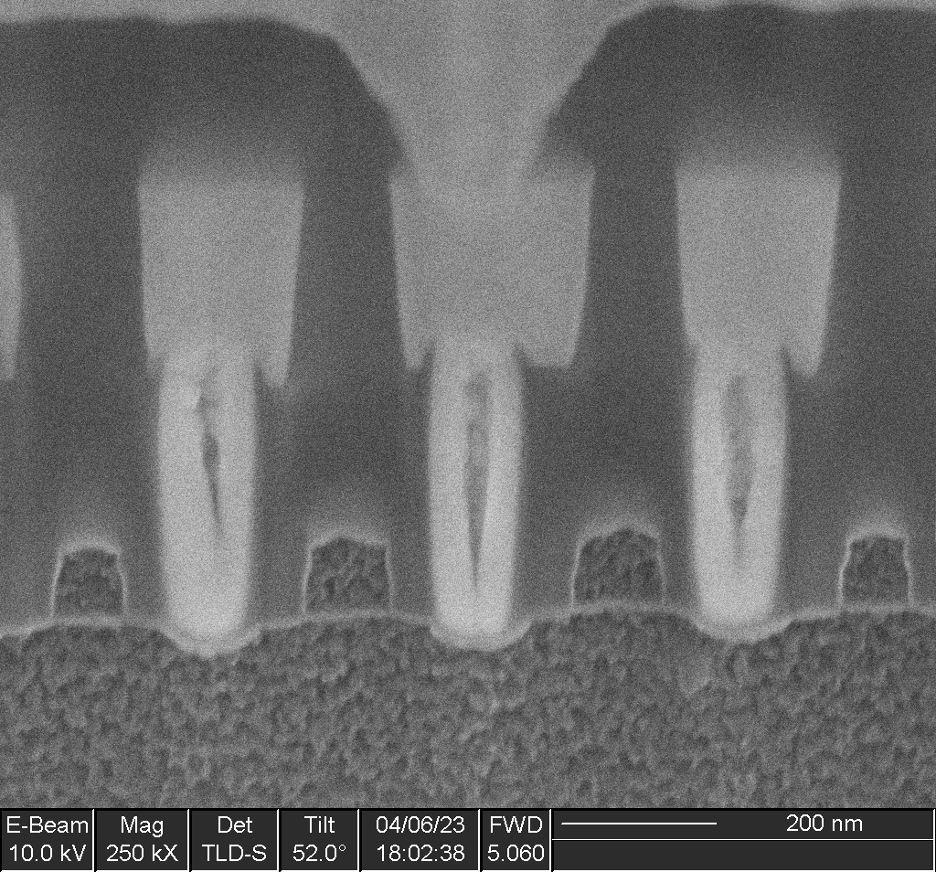

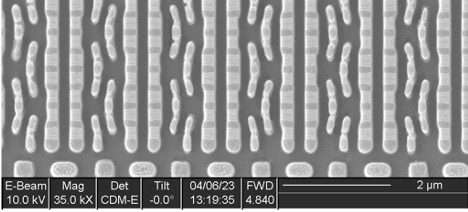

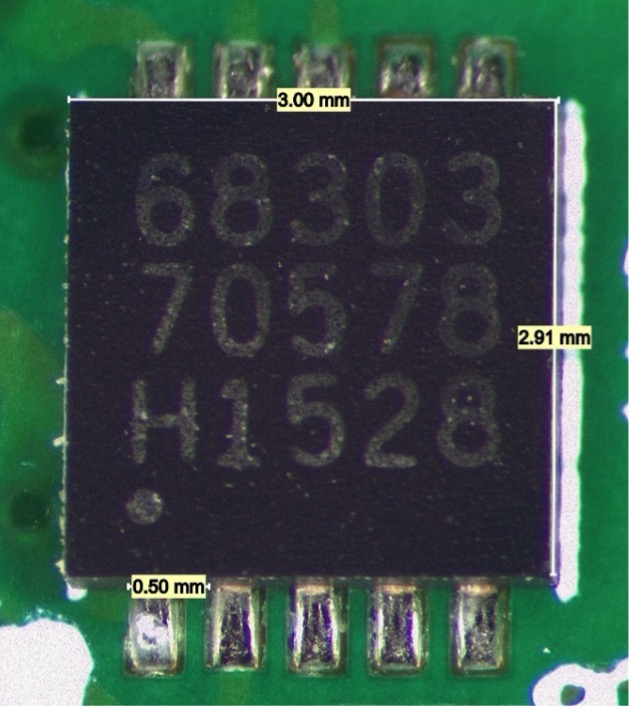

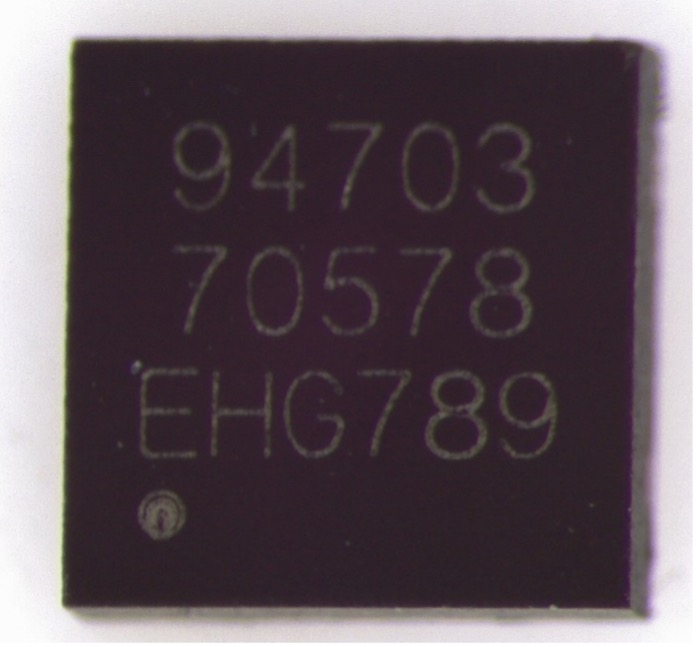

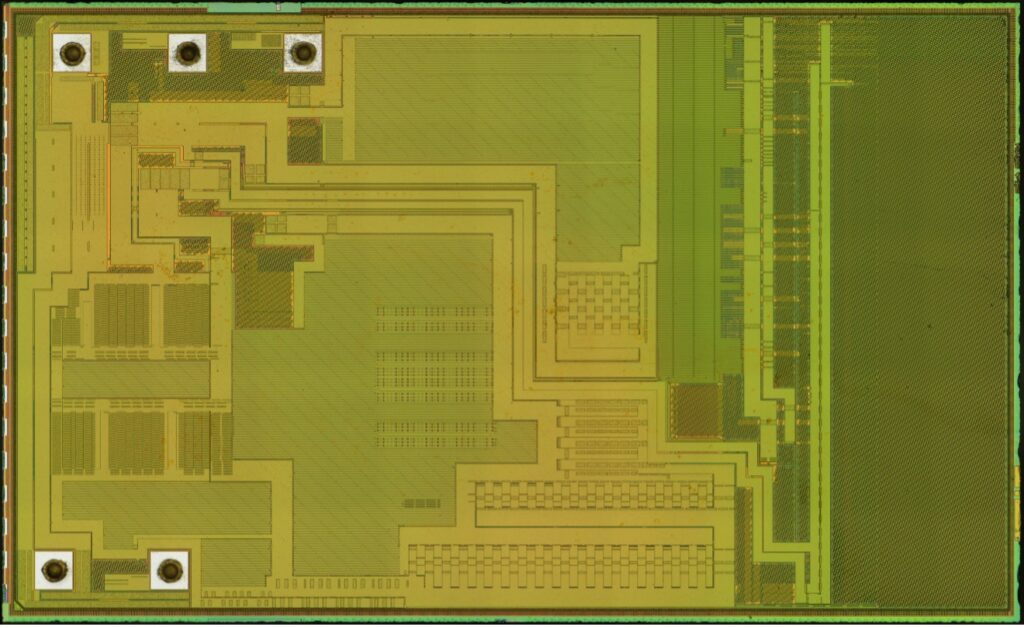

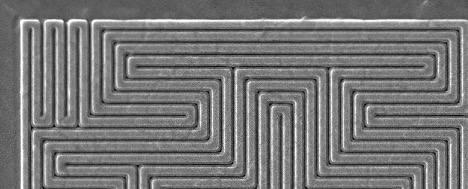

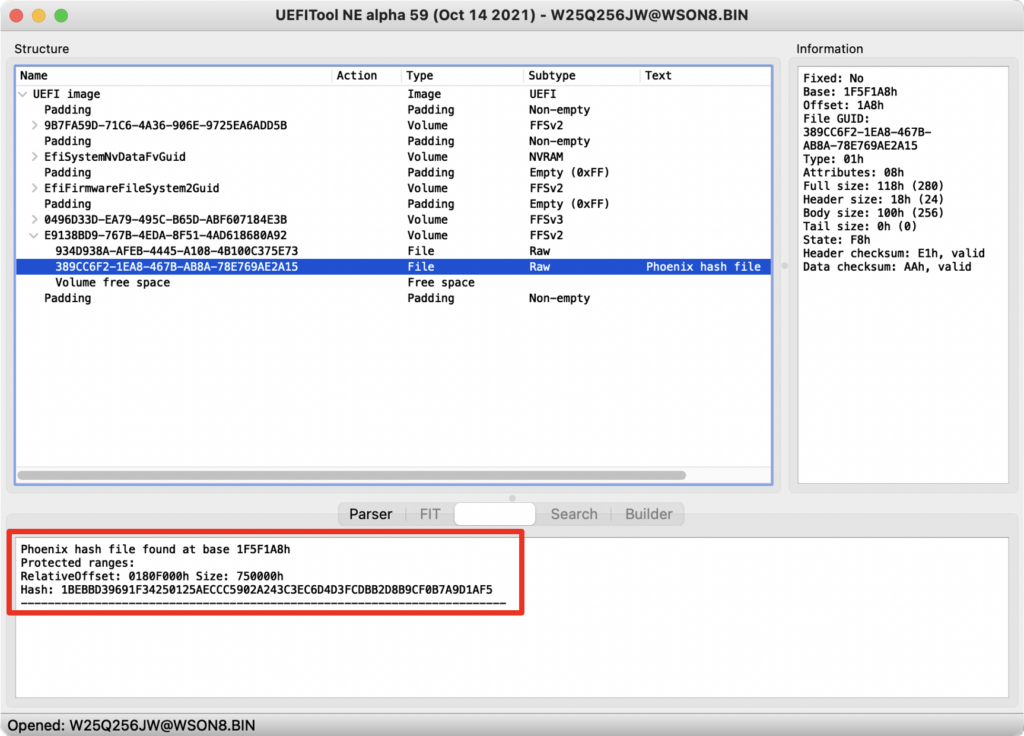

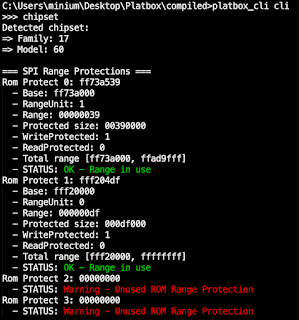

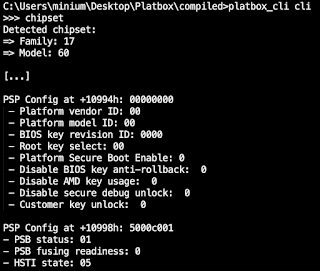

To begin, we picked the Lenovo Thinkpad P16s Gen1 (BIOS v1.32) as our target, as it was one of the few systems that had the PSB enabled, and inspected the firmware with UEFI Tool. As it turns out, it uses a Phoenix-based BIOS and a well-known data structure, called the Phoenix hash file, to verify the DXE phase:

The Phoenix hash file format is straightforward – it is a list of protected ranges of the SPI flash encoded using triples that consist of base address, size and a hash. These protected ranges should, at least in theory, cover the DXE phase code, stored in DXE firmware volumes, that will be loaded.

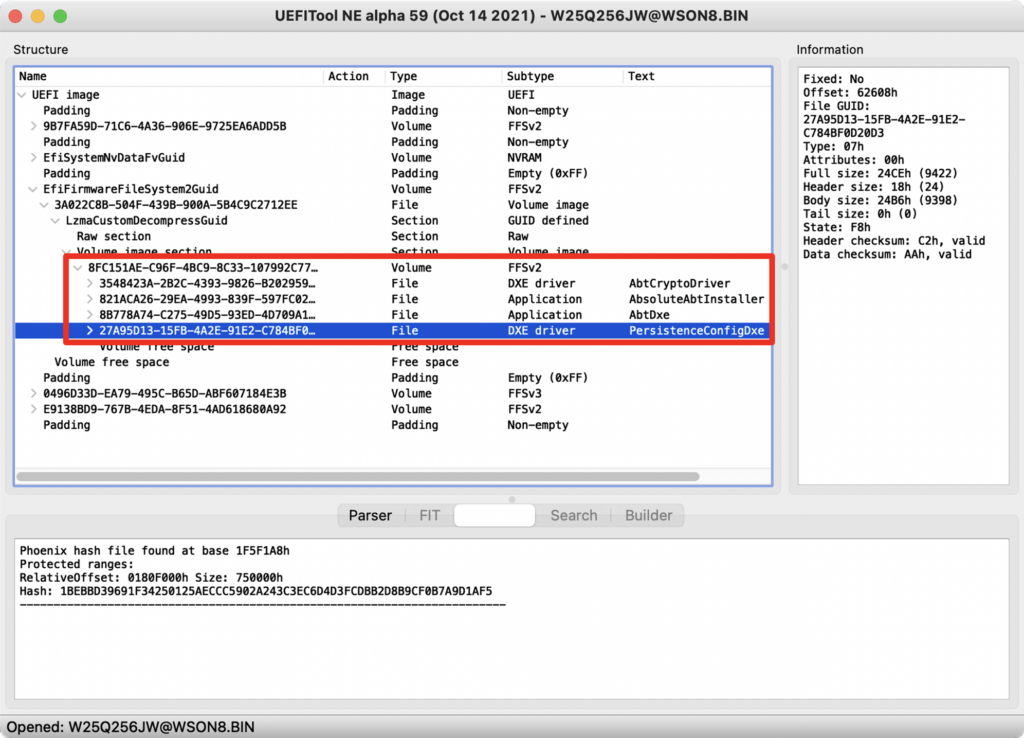

However, we found that that multiple firmware volumes were used and that one of them (GUID 8FC151AE-C96F-4BC9-8C33-107992C7735B) was not covered by the protected ranges. Thereby, code contained within said volume could be tampered with and it would be automatically loaded during the boot process.

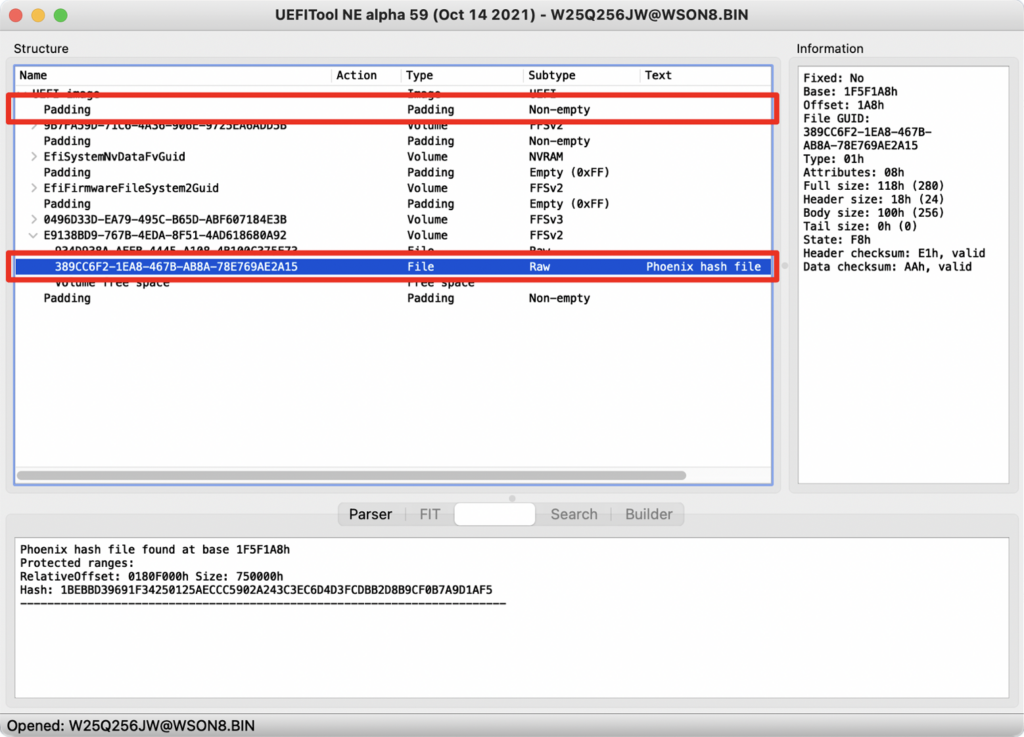

To make matters worse, we noticed that while the BIOS PEI firmware volume, verified by the PSP, was located in the beginning of the firmware in the padding section, whereas the Phoenix hash file was located at the end of it and thereby could be tampered with.

To confirm that the issue was indeed exploitable, we replaced the PersistenceConfigDxe DXE driver (GUID 27A95D13-15FB-4A2E-91E2-C784BF0D20D3) with a malicious DXE driver that configures the SMM_KEY MSR and allows us, at runtime, to disable the TSEG protections and thereby trivially escalate privileges to SMM (see previous blog post for more details).

Note that an advisory was published by Lenovo (see here) for this vulnerability (assigned CVE-2023-5078) that details which systems it affected and when different BIOS updates were released.

Vendor response

As part of our responsible disclosure process, we have reached out to various vendors in order to address the issues and get an understanding of the underlying problem. The responses were, to say the least, quite surprising:

Acer

“We appreciated your information about a possible vulnerability in Acer product. After thoroughly investigation, AMD PSB is an Optional Design during develop on consumption product, it’s not a mandatory requirement in Swift 3 SF314-42;

even though AMD PSB status is not enabled by default, platform with Secure Boot and Secure Flash are in position to protect system if malicious code injecting to flash ROM, so we don’t consider this as a vulnerability.”

Lenovo

“Platform Secure Boot was introduced as a standard feature on all consumer Lenovo laptops in 2022, and laptops manufactured prior to this date were not designed with this feature in mind. Enabling it on devices now in the field would be likely to frustrate consumers if any unexpected issues arise.”

Huawei

“The PSB function was not enabled on our early AMD platform product, the PSB-like function(also known as “Intel Boot Guard”) was enabled on our later Intel platform product (such as MateBook 16s 2022).

We confirmed with the BIOS supplier (Wingtech Technology) of the AMD platform product, there is no modification plan for this issue. To avoid confusing users, we kindly ask you not to disclose this issue. […]”

Conclusions

The results of our research demonstrate how vendors systematically failed to either properly configure the platform or correctly implement the chain-of-trust. Although it is clear how this issue needs to be addressed, based on vendor responses, it appears that they are reluctant to do so.

These issues would allow an attacker that has obtained a foothold on the OS, in combination with a SPI flash write primitive (e.g. CVE-2023-28468), to install firmware implants on the system. These, by design, bypass any OS- and Hypervisor-level protections that may be implemented and, if done properly, can also be made resistant to traditional firmware updates.

To determine whether you are vulnerable, we recommend running our in-house developed tool Platbox (see here) and, if that is the case, to reach out to the vendor in the hope that they will address these issues.

Appendix

The following table lists the systems we tested and what we discovered.